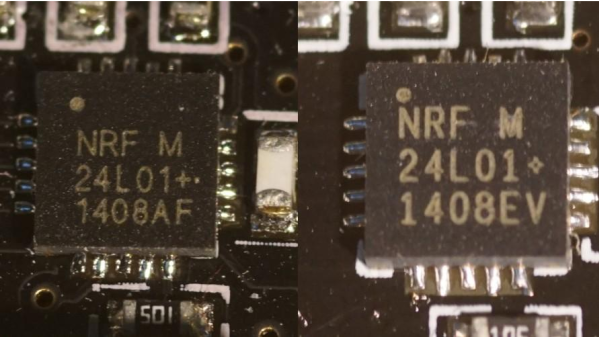

The Nordic Semiconductor nRF24L01 is the older sibling of the nRF24L01+ and is not recommended for new designs anymore. Sometimes, if you’re looking for a cheaper bargain, the older chip may the way to go. [necromant] recently got hold of a bunch of cheap nrf24l01 modules. How cheap ? Does $0.55 sound cheap enough?

Someone back east worked out how to cost-optimize cheap modules and make them even cheaper. At that price, the modules would have severe performance limitations, if they worked at all. [necromant] decided to take a look under the hood. First off, there’s no QFN package on the modules. Instead they contain a COB (chip on board) embedded in black epoxy. [necromant] guesses it’s most likely one of those fake ASICs under the epoxy with more power consumption and less sensitivity. But there’s a step further you can go in making it cheaper. He compared the modules to the reference schematics, and found several key components missing. A critical current set resistor is missing (unless it’s hiding under the epoxy). And many of the components on the transmit side are missing – which means signal power would be nowhere near close to the original modules.

The big question is if they work or not ? In one test, the radio did not work at all. In a different setup, it worked, albeit with very low signal quality. If you are in Moscow, and have access to 2.4Ghz RF analysis tools, [necromant] would like to hear from you, so he can look at the guts of these modules.

Thanks to [Andrew] for sending in this tip.

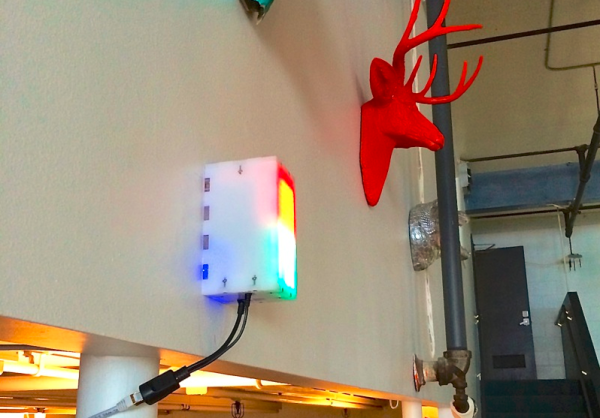

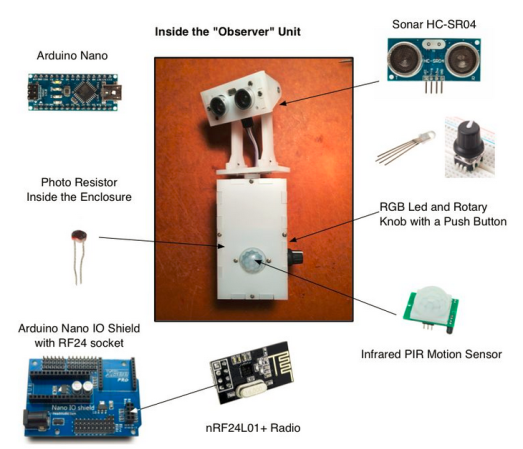

[kigster] began work on BORAT: Bathroom Occupancy Remote Awareness Technology. The initial problem was detecting bathroom occupancy. The easiest method would be to use door locks with embedded switches, much those used in aircraft. Unfortunately, modifying or changing the locks in a rented office space is a big no-no. Several other human detection systems were suggested and rejected. The final solution was a hybrid. Sonar, Passive Infrared (PIR), and light sensors work in concert to detect if a person is in the bathroom. While we think the final “observer unit” is rather cool looking, we’re sure unsuspecting visitors to the office may be wondering why a two eyed robot is staring at them on the throne.

[kigster] began work on BORAT: Bathroom Occupancy Remote Awareness Technology. The initial problem was detecting bathroom occupancy. The easiest method would be to use door locks with embedded switches, much those used in aircraft. Unfortunately, modifying or changing the locks in a rented office space is a big no-no. Several other human detection systems were suggested and rejected. The final solution was a hybrid. Sonar, Passive Infrared (PIR), and light sensors work in concert to detect if a person is in the bathroom. While we think the final “observer unit” is rather cool looking, we’re sure unsuspecting visitors to the office may be wondering why a two eyed robot is staring at them on the throne.