There’s no rule that says that logic circuits must always use electrically conductive materials, which is why you can use water, air or even purely mechanical means to implement logic circuits. When it comes to [soiboi soft]’s squishy robots, it thus makes sense to turn the typical semiconductor control circuitry into an air-powered version as much as possible.

We previously featured the soft and squishy salamander robot that [soiboi] created using pneumatic muscles. While rather agile, it still has to drag a whole umbilical of pneumatic tubes along, with one tube per function. Most of the research is on microfluidics, but fortunately air is just a fluid that’s heavily challenged in the density department, allowing the designs to be adapted to create structures like gates and resistors.

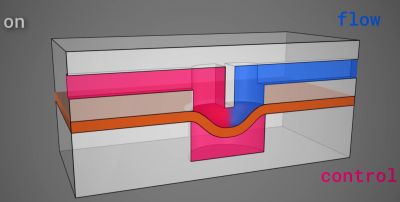

Logically, a voltage potential or a pressure differential isn’t so different, and can be used in a similar way. A transistor for example is akin to the vacuum tube, which in British English is called a valve for good reason. Through creative use of a flexible silicone membrane and rigid channels, pulling a vacuum in the ‘gate’ channel allows flow through the other two channels.

Similarly, a ‘resistor’ is simply a narrowing of a channel, thus resisting flow. The main difference compared to the microfluidics versions is everything is a much larger scale. This does make it printable on a standard FDM printer, which is a major benefit.

Quantifying these pneumatic resistors took a bit of work, using a pressure sensor to determine their impact, but after that the first pneumatic logic circuits could be designed. The resistors are useful here as pull-downs, to ensure that any charge (air) is removed, while not impeding activation.

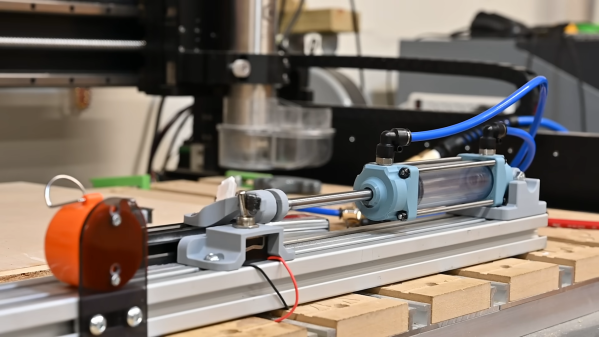

The design, as shown in the top image, is a 5-stage ring oscillator that provides locomotion to a set of five pneumatic muscles. As demonstrated at the end of video, this design allows for the entire walking motion to be powered using a single input of compressed air, not unlike the semiconductor equivalent running off a battery.

While the somewhat bulky nature of pneumatic logic prevents it from implementing very complex logic, using it for implementing something as predictable as a walking pattern as demonstrated seems like an ideal use case. When it comes to making these squishy robots stand-alone, it likely can reduce the overall bulk of the package, not to mention the power usage. We are looking forward to how [soiboi]’s squishy robots develop and integrate these pneumatic circuits.

Continue reading “Printing An Air-Powered Integrated Circuit For Squishy Robots”