One of the blockbuster talks at last year’s Chaos Communications Congress covered how a group of hackers discovered code that allegedly bricked public trains in Poland when they went into service at a competitor’s workshop. This year, the same group is back with tales of success, lawsuits, and appearances in the Polish Parliament. You’re not going to believe this, but it’s hilarious.

The short version of the story is that [Mr. Tick], [q3k], and [Redford] became minor stars in Poland, have caused criminal investigations to begin against the train company, and even made the front page of the New York Times. Newag, the train manufacturer in question has opened several lawsuits against them. The lawsuit alleges the team is infringing on a Newag copyright — by publishing the code that locked the trains, no less! If that’s not enough, Newag goes on to claim that the white hat hackers are defaming the company.

What we found fantastically refreshing was how the three take all of this in stride, as the ridiculous but incredibly inconvenient consequences of daring to tell the truth. Along the way they’ve used their platform to speak out for open-sourcing publicly funded code, and the right to repair — not just for consumers but also for large rail companies. They are truly fighting the good fight here, and it’s inspirational to see that they’re doing so with humor and dignity.

If you missed their initial, more technical, talk last year, go check it out. And if you ever find yourself in their shoes, don’t be afraid to do the right thing. Just get a good lawyer.

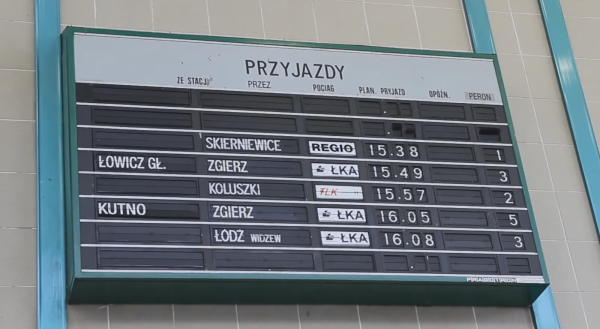

The system runs on punch cards. You can’t buy them anymore, so a local printer makes them – several hundred are needed every time there is a schedule change. The punching pliers (which also can no longer be purchased) get so worn out they replace the pins with custom-made ones from a local locksmith. The moving parts of the card reader have split-pins which need to be replaced every week or two – the stress of repeated movement simply wears them away. There’s nothing to do but replace them regularly. The assembly needs regular cleaning since dust accumulates on the cards and gets into the whole assembly. The list goes on… and so does the station.

The system runs on punch cards. You can’t buy them anymore, so a local printer makes them – several hundred are needed every time there is a schedule change. The punching pliers (which also can no longer be purchased) get so worn out they replace the pins with custom-made ones from a local locksmith. The moving parts of the card reader have split-pins which need to be replaced every week or two – the stress of repeated movement simply wears them away. There’s nothing to do but replace them regularly. The assembly needs regular cleaning since dust accumulates on the cards and gets into the whole assembly. The list goes on… and so does the station.