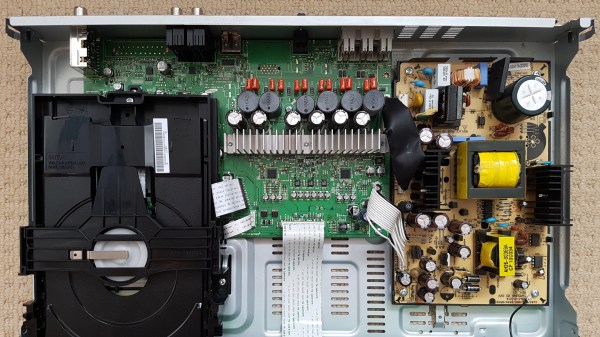

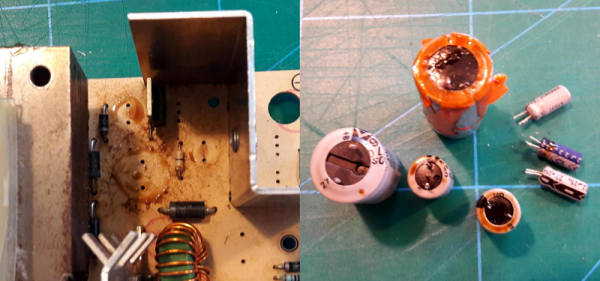

Old electrolytic capacitors are notorious for not working like they used to, but what exactly does a bad capacitor look like, and what kinds of problems can it cause? Usually bad caps leak or bulge, but not always. In [Zak Kemble]’s case, a bad cap caused his Samsung HT-C460 Home Cinema System to simply display “PROT” then turn itself off. Luckily, replacing the troublesome cap fixed everything, but finding the problem in the first place wasn’t quite so straightforward. A visual inspection of the device, shown open in the photo above, didn’t reveal any obvious problems. None of the capacitors looked anything out of the ordinary, but one of them turned out to be the problem anyway.

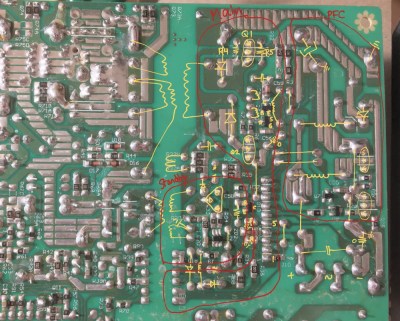

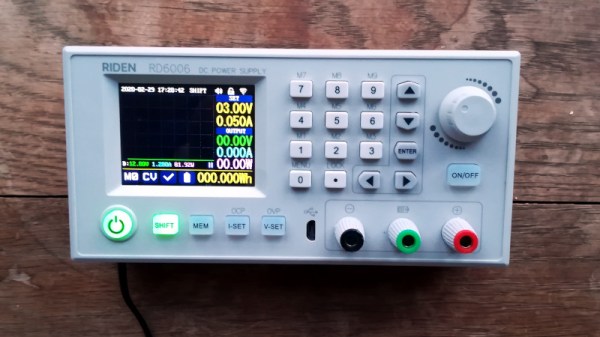

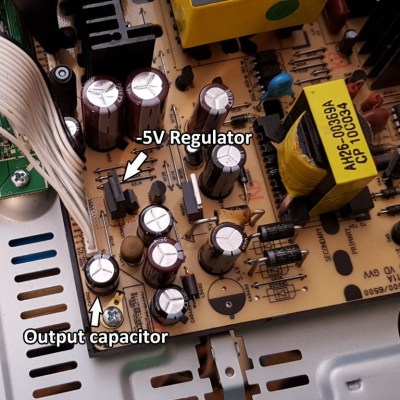

The first identifiable issue was discovering that the -5 V supply was only outputting about -0.5 V, and there was a 6 V drop across two small 0805-sized resistors, evidence that something was sinking far more current than it should.

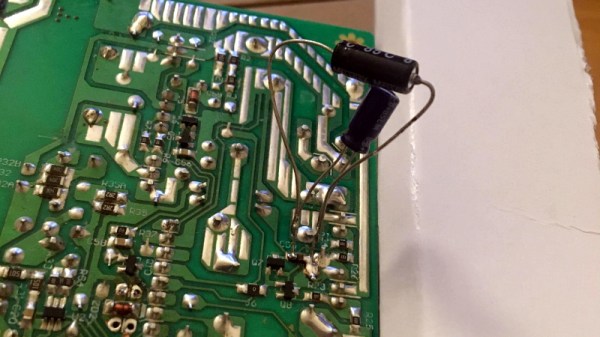

Testing revealed that the -5 V regulator wasn’t malfunctioning, and by process of elimination [Zak] finally removed the 470 uF output capacitor on the -5 V output, and the problem disappeared! Inspecting the capacitor revealed no outward sign of malfunction, but it had developed an internal short. [Zak] replaced the faulty cap (and replaced the others just to be safe) and is now looking forward to getting years more of use out of his home cinema system.

When a PSU gives up the ghost, bad capacitors are almost always to blame, but we’ve seen before that it’s not always easy to figure out which ones are bad. One thing that helped [Zak] plenty in his troubleshooting is finding a full schematic of the power supply, just by doing a search for the part number he found on it. A good reminder that it’s always worth throwing a part number into a search engine; you might get lucky!