Quadcopters are great for maneuverability and slow, stable flight, but it comes at the cost of efficiency. [Peter Ryseck]’s Mini QBIT quadrotor biplane brings in some of the efficiency of fixed-wing flight, without all the complexity usually associated with VTOL aircraft.

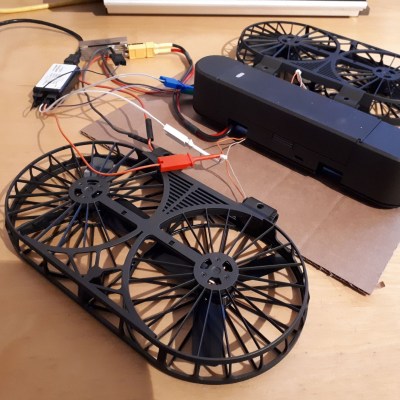

The Mini QBIT is just a 3″ mini quadcopter with a pair of wings mounted below the motors, turning it into a “tailsitter” VTOL aircraft. The wings and nosecone attach to the 3D printed frame using magnets, which allows them to pop off in a crash. There is no need for control surfaces on the wings since all the required control is done by the motors. The QBIT is based on a research project [Peter] was involved in at the University of Maryland. The 2017 paper states that the test aircraft used 68% less power in forward flight than hovering.

(Editor’s Note: [Peter] contacted us directly, and he’s got a newer paper about the aircraft.)

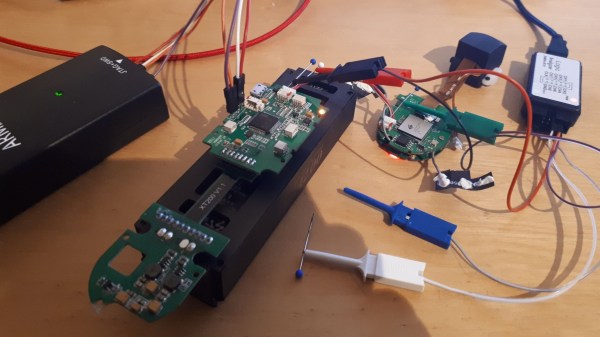

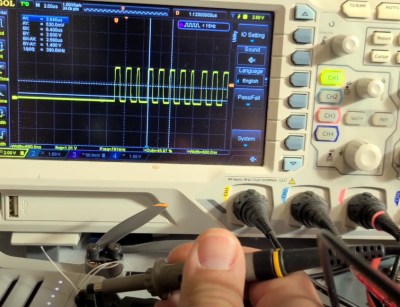

Getting the flight controller to do smooth transitions from hover to forward flight can be quite tricky, but the QBIT does this using a normal quadcopter flight controller running Betaflight. The quadcopter hovers in self-leveling mode (angle mode) and switches to acro mode for forward flight. However, as the drone pitches over for forward flight, the roll axis becomes the yaw axis and the yaw axis becomes the reversed roll axis. To compensate for this, the controller set up to swap these two channels at the flip of a switch. For FPV flying, the QBIT uses two cameras for the two different modes, each with its own on-screen display (OSD). The flight controller is configured to use the same mode switch to change the camera feed and OSD.

[Peter] is selling the parts and STL files for V2 on his website, but you can download the V1 files for free. However, the control setup is really the defining feature of this project, and can be implemented by anyone on their own builds.

For another simple VTOL project, check out [Nicholas Rehm]’s F-35 which runs on his dRehmFlight flight control software. Continue reading “VTOL Tailsitter Flies With Quadcopter Control Software”