There are hundreds of ARM-based Linux development boards out there, with new ones appearing every week. The bulk of these ARM boards are mostly unsupported, and in the worst case they don’t work at all. There’s a reason the Raspberry Pi is the best-selling tiny ARM computer, and it isn’t because it’s the fastest or most capable. The Raspberry Pi got to where it is today because of a huge amount of work from devs around the globe.

Try as they might, the newcomer fabricators of these other ARM boards can’t easily glom onto the popularity of the Pi. Doing so would require a Broadcom chipset. Now that the Broadcom BCM2835-based ODROID-W has gone out of production because Broadcom refused to sell the chips, the Raspberry Pi ecosystem has been completely closed.

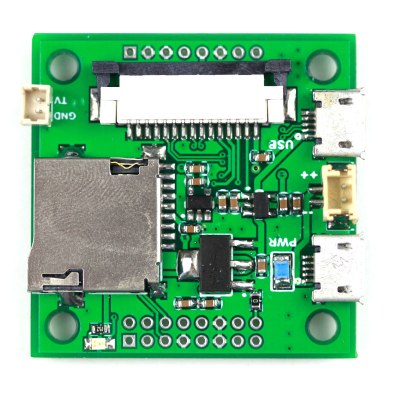

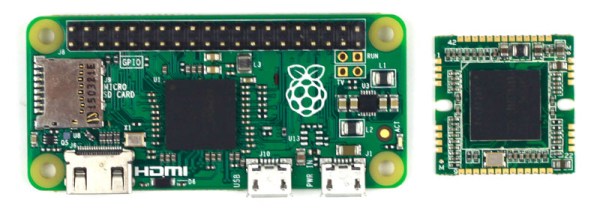

Things may be changing. ArduCAM has introduced a tiny Raspberry Pi compatible module based on Broadcom’s BCM2835 chipset, the same chip found in the original Raspberry Pis A, B, B+ and Zero. This module is tiny – just under an inch square – and compatible with all of the supported software that makes the Raspberry Pi so irresistible.

Although this Raspberry Pi-compatible board is not finalized, the specs are what you would expect from what is essentially a Raspberry Pi Zero cut down to a square inch board. The CPU is listed as, “Broadcom BCM2835 ARM11 Processor @ 700 MHz (or 1GHz?)” – yes, even the spec sheet doesn’t know how fast the CPU is running – and RAM is either 256 or 512MB of LPDDR2.

Although this Raspberry Pi-compatible board is not finalized, the specs are what you would expect from what is essentially a Raspberry Pi Zero cut down to a square inch board. The CPU is listed as, “Broadcom BCM2835 ARM11 Processor @ 700 MHz (or 1GHz?)” – yes, even the spec sheet doesn’t know how fast the CPU is running – and RAM is either 256 or 512MB of LPDDR2.

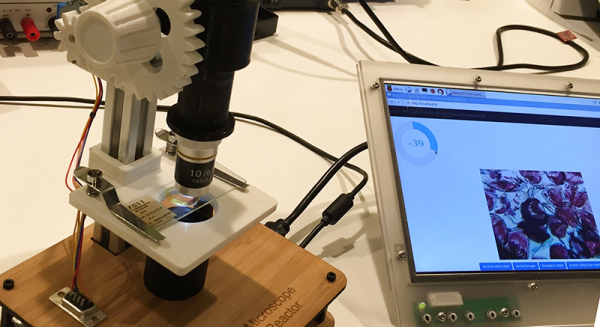

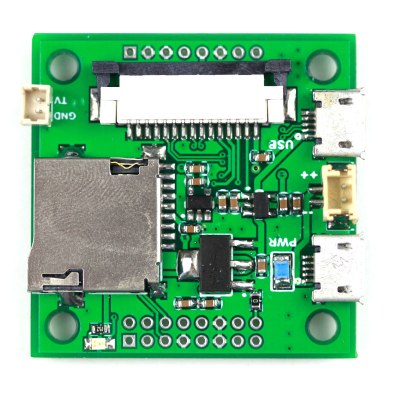

There isn’t space on the board for a 2×20 pin header, but a sufficient number of GPIOs are broken out to make this board useful. You will fin a micro-SD card slot, twin micro-USB ports, connectors for power and composite video, as well as the Pi Camera connector. This board is basically the same size as the Pi Camera board, making the idea of a very tiny Linux-backed imaging systems tantalizingly close to being a reality.

It must be noted that this board is not for sale yet, and if Broadcom takes offense to the project, it may never be. That’s exactly what happened with the ODROID-W, and if ArduCAM can’t secure a supply of chips from Broadcom, this project will never see the light of day.

Although this Raspberry Pi-compatible board is not finalized, the specs are what you would expect from what is essentially a Raspberry Pi Zero cut down to a square inch board. The CPU is listed as, “Broadcom BCM2835 ARM11 Processor @ 700 MHz (or 1GHz?)” – yes, even the spec sheet doesn’t know how fast the CPU is running – and RAM is either 256 or 512MB of LPDDR2.

Although this Raspberry Pi-compatible board is not finalized, the specs are what you would expect from what is essentially a Raspberry Pi Zero cut down to a square inch board. The CPU is listed as, “Broadcom BCM2835 ARM11 Processor @ 700 MHz (or 1GHz?)” – yes, even the spec sheet doesn’t know how fast the CPU is running – and RAM is either 256 or 512MB of LPDDR2.