The public promise of the Internet Of Things from years ago when the first journalists discovered the idea and strove to make it comprehensible to the masses was that your kitchen appliances would be internet-connected and somehow this would make our lives better. Fridges would have screens, we were told, and would magically order more bacon when supplies ran low.

A decade or so later some fridges have screens, but the real boom in IoT applications has not been in such consumer-visible applications. Most of your appliances are still just as unencumbered by connectivity as they were twenty years ago, and that Red Dwarf talking toaster that Lives Only To Toast is still fortunately in the realm of fiction.

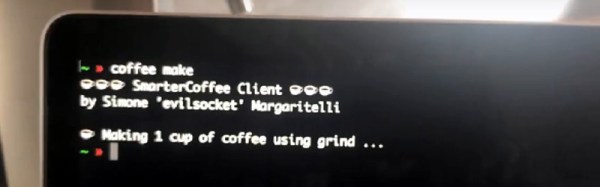

The market hasn’t been devoid of IoT kitchen appliances though. One is the Smarter Coffee coffee machine, a network-connected coffeemaker that is controlled from an app. [Simone Margaritelli] bought one, though while he loved the coffee he really wasn’t keen on its not having a console application. He thus set about creating one, starting with reverse engineering its protocol by disassembling the Android version of its app.

What he found was sadly not an implementation of RFC 2324, instead it uses a very simple byte string to issue commands with parameters such as coffee strength. There is no security, and he could even trigger a firmware upgrade. The app requires a registration and login, though this appears to only be used for gathering statistics. His coffee application can thus command all the machine’s capabilities from his terminal, and he can enjoy a drink without reaching for an app.

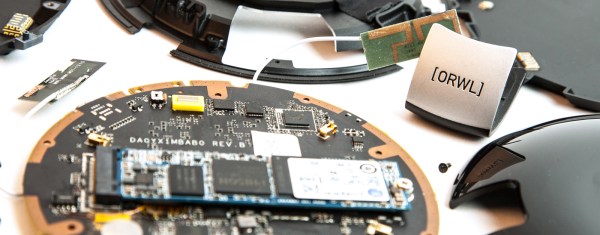

On the face of it you might think that the machine’s lack of security might not matter as it is on a private network behind a firewall. But it represents yet another example of a worrying trend in IoT devices for completely ignoring security. If someone can reach it, the machine is an open book and the possibility for mischief far exceeds merely pranking its owner with a hundred doppio espressos. We have recently seen the first widely publicised DDoS attack using IoT devices, it’s time manufacturers started taking this threat seriously.

If the prospect of coffee hacks interests you, take a look at our previous coverage.

[via /r/homeautomation]