For a lot of us, soldering just seems to come naturally. But if we’re being honest, none of us was born with a soldering iron in our hand — ouch! — and if we’re good at soldering now, it’s only thanks to good habits and long practice. But what if you’re a company that lives and dies by the quality of the solder joints your employees produce? How do you get them to embrace the dark art of soldering?

If you’re Tektronix in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the answer is simple: make in-depth training videos that teach people to solder the Tek way. The first video below, from 1977, is aimed at workers on the assembly line and as such concentrates mainly on the practical aspects of making solid solder joints on PCBs and mainly with through-hole components. The video does have a bit of theory on soldering chemistry and the difference between eutectic alloys and other tin-lead mixes, as well as a little about the proper use of silver-bearing solders. But most of the time is spent discussing the primary tool of the trade: the iron. Even though the film is dated and looks like a multi-generation dupe from VHS, it still has a lot of valuable tips; we’ve been soldering for decades and somehow never realized that cleaning a tip on a wet sponge is so effective because the sudden temperature change helps release oxides and burned flux. The more you know.

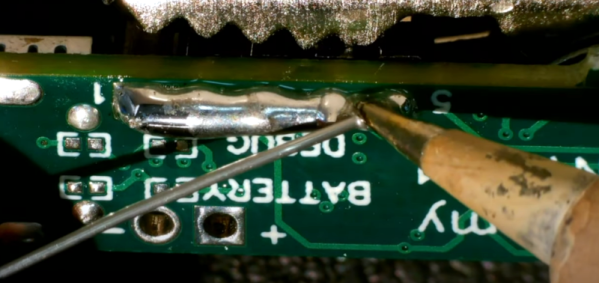

The second video below is aimed more at the Tek repair and rework technicians. It reiterates a lot of the material from the first video, but then veers off into repair-specific topics, like effective desoldering. Pro tip: Don’t use the “Heat and Shake” method of desoldering, and wear those safety glasses. There’s also a lot of detail on how to avoid damaging the PCB during repairs, and how to fix them if you do manage to lift a trace. They put a fair amount of emphasis on the importance of making repairs look good, especially with bodge wires, which should be placed on the back of the board so they’re not so obvious. It makes sense; Tek boards from the era are works of art, and you don’t want to mess with that.