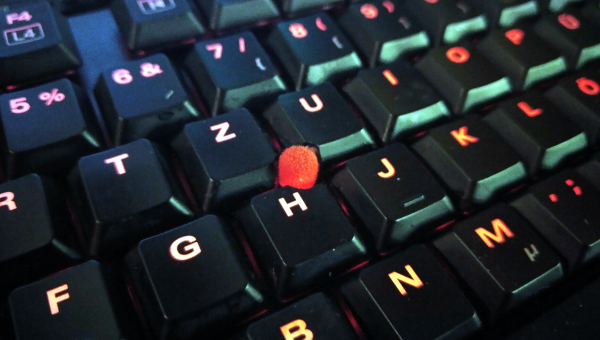

What do you look for in a travel keyboard? For me, it has to be split, though this condition most immediately demands a carrying solution of some kind. Wirelessness I can take or leave, so it’s nice to have both options available. And of course, bonus points if it looks so good that people interrupt me to ask questions.

You’ll see a couple of really neat features, like swing-out tenting feet, a trackpoint, rotary encoders, and the best part of all — a carrying case that doubles as a laptop stand. Sweet!

Eight years in the making, this is the fifth in a series, thus the name: the P stands for Portability; the S for Split. [kleshwong] believes that 36 keys is just right, as long as you have what you need on various layers.

So, do what you can in the like/share/subscribe realm so we can all see the GitHub come to pass, would you? Here’s the spot to watch, and you can enjoy looking through the previous versions while you wait with your forks and stars.

Continue reading “Keebin’ With Kristina: The One With The Ultimate Portable Split”