If you’ve ever wondered why NTSC video is 30 frames and 60 fields a second, it’s because the earliest televisions didn’t have fancy crystal oscillators. The refresh rate of these TVs was controlled by the frequency of the power coming out of the wall. This is the same reason the PAL video standard exists for countries with 50Hz mains power, and considering how inexpensive this method of controlling circuits was the trend continued and was used in clocks as late as the 1980s. [Ch00f] wondered how accurate this 60Hz AC was, so he designed a little test.

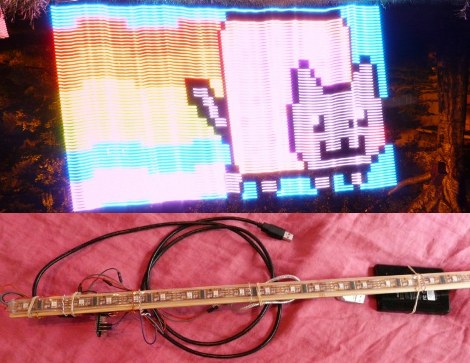

Earlier this summer, [Ch00f] bought a 194 discrete transistor clock kit and did an amazing job tearing apart the circuit figuring out how the clock keeps time. Needing a way to graph the frequency of his mains power, [Ch00f] took a small transformer and an LM311 comparator. to out put a 60Hz signal a microcontroller can read.

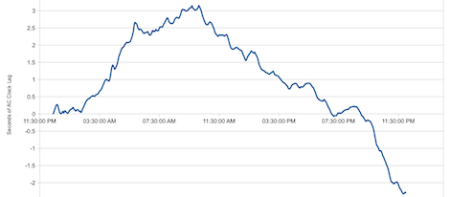

This circuit was attached to a breadboard containing two microcontrollers, one to keep time with a crystal oscillator, the other to send frequency data over a serial connection to a computer. After a day of collecting data, [Ch00f] had an awesome graph (seen above) documenting how fast or slow the mains frequency was over the course of 24 hours.

The results show the 60Hz coming out of your wall isn’t extremely accurate; if you’re using mains power to calibrate a clock it may lose or gain a few seconds every day. This has to do with the load the power companies see explaining why changes in frequency are much more rapid during the day when load is high.

In the end, all these changes in the frequency of your wall power cancel out. The power companies do the same thing [Ch00f] did and make sure mains power is 60Hz over the long-term, allowing mains-controlled clocks to keep accurate time.