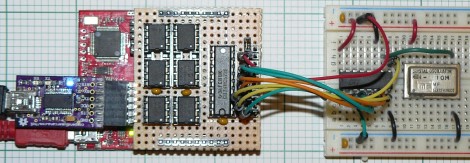

Sure, it’s probably a gimmick to [Jon Masters], but we absolutely love the pedal-powered server he built using a group of ARM chips. [Jon] is an engineer at Red Hat and put together the project in order to show off the potential of the low-power ARM offerings.

The platform is a quad-core Calxeda EnergyCore ARM SoC. Each chip draws only 5 Watts at full load, with eight chips weighing in at just 40 Watts. The circuit to power the server started as a solar charger, which was easy to convert just by transitioning from panels to a generator that works just like a bicycle trainer (the rear wheel presses against a spin wheel which drives the generator shaft).

So, the bicycle generator powers the solar charger, which is connected to an inverter that feeds a UPS. After reading the article and watching the video after the break we’re a bit confused on the actual setup. We would think that the inverter would feed the charger but that doesn’t seem to be the case here. If you can provide some clarity on how the system is connected please feel free to do so in the comments.