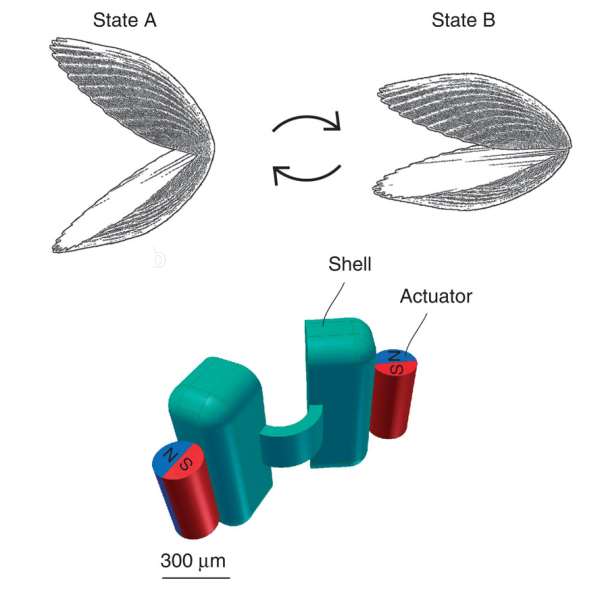

The idea of using nanobots to treat diseases has been around for years, though it has yet to be realized in any significant manner. Inspired by Purcell’s Scallop theorem, scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems have created their own version . They designed a “micro-scallop” that could propel itself through non-Newtonian fluids, which is what most biological fluids happen to be.

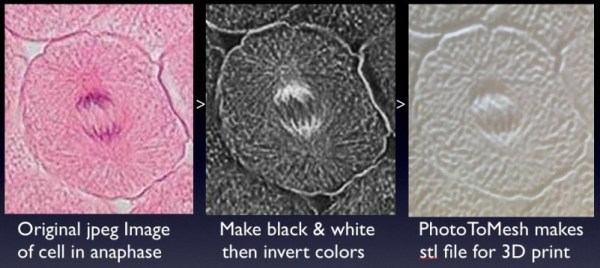

The scientists decided on constructing a relatively simple robot, one with two rigid “shells” and a flexible connecting hinge. They 3D-printed a negative mold of the structure and filled it with a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) solution mixed with fluorescent powder to enable detection. Once cured, the nanobot measured 800 microns wide by 300 microns thick. It’s worth noting that it did not have a motor. Once the mold was complete, two neodymium magnets were glued onto the outside of each shell. When a gradient-free external magnetic field was applied, the magnets make the nanobot’s shells open and close. These reciprocal movements resulted in its net propulsion through non-Newtonian media. The scientists also tested it in glycerol, an example of a Newtonian fluid. Confirming Purcell’s Scallop theorem, the nanobot did not move through the glycerol. They took videos of the nanobot in motion using a stereoscope, a digital camera with a colored-glass filter, and an ultraviolet LED to make the fluorescent nanobot detectable.

The scientists did not indicate any further studies regarding this design. Instead, they hope it will aid future researchers in designing nanobots that can swim through blood vessels and body fluids. We don’t know how many years it will be before this becomes mainstream medical science, but we know this much: we will never look at scallops the same way again!

Continue reading “Nanobots Swim Like Scallops In Non-Newtonian Fluids”