We recently ran a post about engineers being worse, better, or the same than they “used to be” and it got me thinking. Of course “used to be” is in the eyes of the beholders. To me, that’s the 1950s and 1960s. To some of you, my generation is the “used to be” generation. To some of you, I’m past even that.

I’ve often said, there are two things that are simple: something really simple, and something really complex. For example, when a caveman grabbed a log floating down the river and hitched a ride a few miles downstream that was pretty simple. Today, you can go on a well-equipped boat, stab your finger at a map, click go, and the boat will do almost all the work. However, get onboard a sailing vessel from 1850 and you better know what you are doing. What’s more is, some sailors were better than others.

What’s Better or Best?

Were yesterday’s engineers better than today? That’s like asking who is the “best” driver. It depends a lot on what “best” means. Safer? Faster? Most efficient? I would suggest that yesterday’s engineers were better at doing yesterday’s jobs. I own several slide rules and I can use them, but I bet my mentor who finished college in the 1940s was faster. I don’t need to be faster. On the other hand, he might have some trouble doing a good Internet search.

But here’s the problem. Doing basic math is like the caveman on the log (and yes, that begs for a slide rule joke). Asking Wolfram Alpha to solve your set of simultaneous equations is like the modern computer-controlled ship with GPS. You can bet that the sailing master of a barque in 1850 knew a lot more about sailing and winds and ship construction than the average guy on a modern ship. He had to. That gave him extra reasoning tools when faced with a problem.

Slide Rules Do (Most) of the Math

By the same token, using a slide rule is very helpful but–paradoxically–you have to know a little math to be able to use it. In particular, you had to have a rough idea of the magnitude of the answer to get the right answer. If you couldn’t get that concept or do the simple estimate in your head, the slide rule was useless and you probably dropped out of engineering school. Today, you may or may not have that kind of math smarts, and it doesn’t matter.

I’ve known graybeards that keep up with the modern technology. I’ve also known plenty who are stuck in the past, talking about how horrible transistors, or ICs, or software is and how it has ruined everything. Of course, they haven’t.

Lesson Learned

As Gerrit pointed out, we tend to remember the brilliant engineers and projects and forget the bad ones (unless they are really bad). Even in “the golden age” there were good engineers and bad.

So how can you maximize your chances of being one of the good ones when this turns into some kid’s golden age? Two things, I think. Never stop learning the new technology. The hot-shot engineer with the slide rule wouldn’t function as well in today’s world unless he was willing to learn about the new things. But also, learn the fundamentals. You don’t have to know how an engine works to drive a car. But all the race car drivers do know. Having tools to do circuit analysis or solve thorny math equations is a great time saver. But you ought to know how to do it without those tools. The insights you’ll gain will give you more tools at your disposal when faced with a problem.

Engineering is a series of abstractions. Always try to drive down the abstraction layers. Know how to program? How does a CPU work at the logic gate level? Know how that works? Then how do the transistors form those gates? When you understand that, dig into why the transistors work at all. Sure, you probably aren’t going to build a transistor from raw materials. But you’ll gain new insights and those insights will help you solve future problems. Besides, if there’s ever a zombie apocalypse, it might be good to know how to use a slide rule or build a transistor.

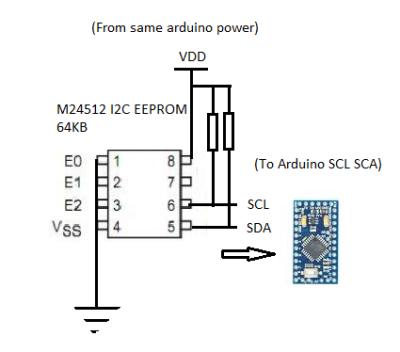

This parts order is for the badge hacking at this year’s

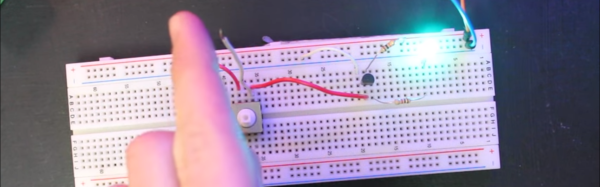

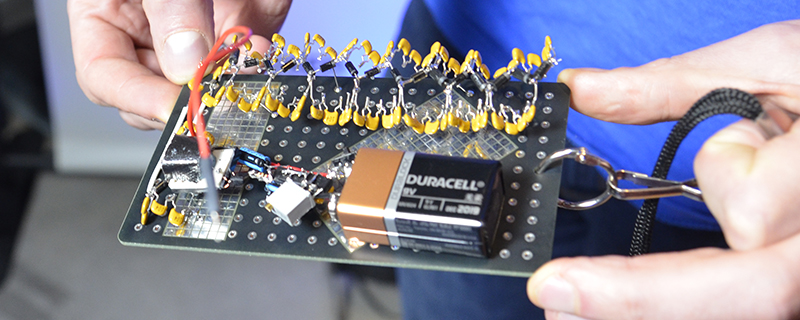

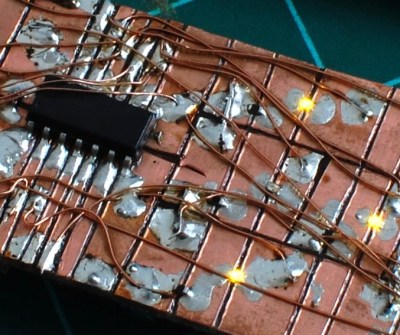

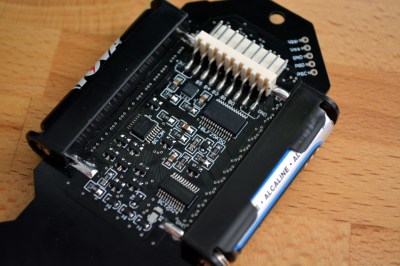

This parts order is for the badge hacking at this year’s  Part of the fun last year was starting from a badge that had no circuitry built onto it at all. [Brian Benchoff] joked in his coverage of the hacking that this year’s badge would just be a piece of copper clad FR4 — a great idea and challenge accepted. In addition to the normal badge, for those willing to test their mettle, we want you to go for Beast Mode. We’ll have copper clad (single and double-sided) and protoboard on hand.

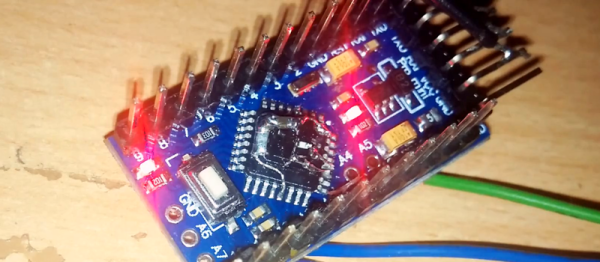

Part of the fun last year was starting from a badge that had no circuitry built onto it at all. [Brian Benchoff] joked in his coverage of the hacking that this year’s badge would just be a piece of copper clad FR4 — a great idea and challenge accepted. In addition to the normal badge, for those willing to test their mettle, we want you to go for Beast Mode. We’ll have copper clad (single and double-sided) and protoboard on hand. Yes, there is a hardware badge and it’s a doozy this year. Voja Antonic designed it and

Yes, there is a hardware badge and it’s a doozy this year. Voja Antonic designed it and