Interplanetary probes were a constant in the tech news bulletins of the 1960s and 1970s. The Space Race was at its height, and alongside their manned flights the two superpowers sent unmanned missions throughout the Solar System. By the 1980s and early 1990s the Space Race had cooled down, the bean counters moved in, and aside from the spectacular images of the planets periodically arriving from the Voyager series of craft there were scant pickings for the deep space enthusiast.

The launch in late 1996 of the Mars Pathfinder mission with its Sojourner rover then was exciting news indeed. Before Spirit, the exceptionally long-lived Opportunity, and the relatively huge Curiosity rover (get a sense of scale from our recent tour of JPL), the little Sojourner operated on the surface of the planet for 85 days, and proved the technology for the rovers that followed.

In these days of constant online information we’d see every nuance of the operation as it happened, but those of us watching with interest in 1997 missed one of the mission’s dramas. Pathfinder’s lander suffered what is being written up today as the first bug on Mars. When the lander collected Martian weather data, its computer would crash.

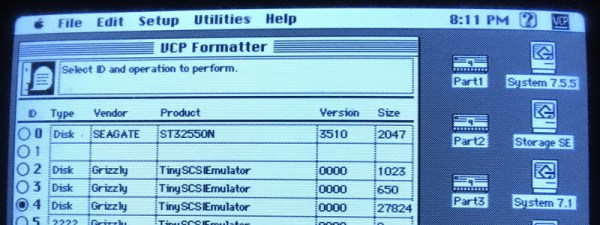

Like many other spacecraft, the lander’s computer system ran the real-time OS VxWorks. Of the threads running on the craft, the weather thread was a low priority, while the more important task of servicing its information bus was a high priority one. The weather task would hog the resources, causing the operating system equivalent of an unholy row in our Martian outpost. A priority inversion bug, and one that had been spotted before launch but assigned a low priority.

You can’t walk up to a computer on another planet and swap out a few disks, so the Pathfinder team had to investigate the problem on their Earthbound replica of the lander. The fix involved executing some C code on an interpreter prompt on the spacecraft itself, something that would give most engineers an extremely anxious moment.

The write-up is an interesting read, it’s a translation from a Russian original that is linked within it. If the work of the JPL scientists and engineers interests you, this talk from the recent Hackaday superconference might be of interest.

[via Hacker News]