Every day, we see people building things. Sometimes, useful things. Very rarely, this thing becomes a product, but even then we don’t hear much about the ins and outs of manufacturing a bunch of these things or the economics of actually selling them. This past weekend at Shmoocon, [Conor Patrick] gave the crowd the inside scoop on selling a few hundred two factor authentication tokens. What started as a hobby is now a legitimate business, thanks to good engineering and abusing Amazon’s distribution program.

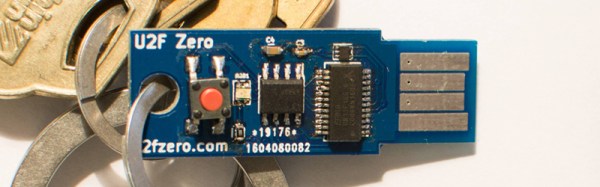

The product in question is the U2F Zero, an open source U2F token for two-factor authentication. It’s built around the Atmel/Microchip ATECC508A crypto chip and is, by all accounts, secure enough. It’s also cheap at about $0.70 a piece, and the entire build comes to about $3 USD. All of this is hardware, and should be extremely familiar to the regular Hackaday reader. This isn’t the focus of [Conor]’s talk though. The real challenge is how to manufacture and sell these U2F dongles, a topic we looked in on back in September.

The circuit for this U2F key is basically just a crypto chip and a USB microcontroller, each of which needs to be programmed separately and ideally securely. The private key isn’t something [Conor] wants to give to an assembly house, which means he’s programming all these devices himself.

For a run of 1100 units, [Conor] spent $350 on PCB, $3600 for components and assembly, $190 on shipping and tariffs from China, and an additional $500 for packaging on Amazon. That last bit pushed the final price of the U2F key up nearly 30%, and packaging is something you have to watch if you ever want to sell things of your own.

For distribution, [Conor] chose Fulfillment By Amazon. This is fantastically cheap if you’re selling a product that already exists, but of course, [Conor]’s U2F Zero wasn’t already on Amazon. A new product needs brand approval, and Amazon would not initially recognize the U2F Zero brand. The solution to this was for [Conor] to send a letter to himself allowing him to use the U2F Zero brand and forward that letter to the automated Amazon brand bot. Is that stupid? Yes. Did it work? Also yes.

Sales were quiet until [Conor] submitted a tip to Hacker News and sold about 70 U2F Zeros in a day. After that, sales remained relatively steady. The U2F Zero is now a legitimate product. Even though [Conor] isn’t going to get rich by selling a dozen or so U2F keys a day, it’s still an amazing learning experience and we’re glad to have sat in on his story of bootstrapping a product, if only for the great tip on getting around Amazon’s fulfillment policies.