If you were a child of the late 1970s or early 1980s, the chances are that your number one desire was to own a games console. The one to have was the Atari 2600, notwithstanding that dreadful E.T. game.

Of course, there were other consoles during that era. One of these also-ran products came from Coleco, a company that had started in the leather business but by the mid 1970s had diversified into handheld single-game consoles. Their ColecoVision console of 1982 sold well initially, but suffered badly in the video game crash of 1983. By 1985 it was gone, and though Coleco went on to have further success, by the end of the decade they too had faded away.

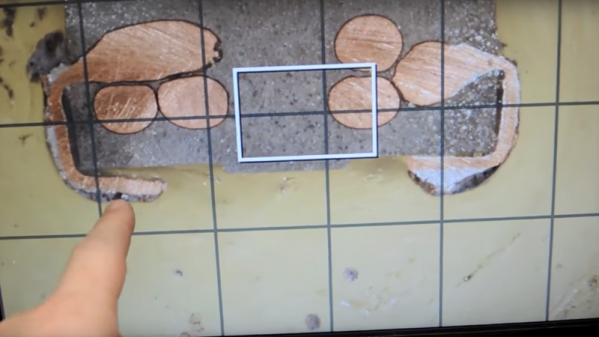

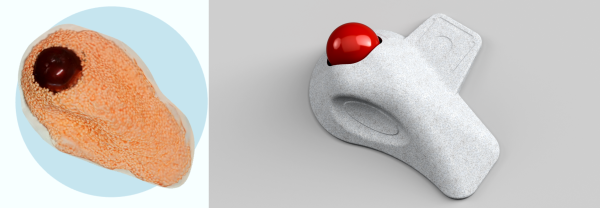

The Coleco story was not over though, because in 2005 the brand was relaunched by a successor company. Initially it appeared on an all-in-one retro console, and then on an abortive attempt to crowdfund a new console, the Coleco Chameleon. This campaign came to a halt after the Chameleon prototypes were shown to be not quite what they seemed by eagle-eyed onlookers. Continue reading “Coleco In Spat With ColecoVision Community”