With the advent of low-cost software defined radio (SDR), anyone who’s interested can surf the airwaves from the FM band all the way up to the gigahertz frequencies used by geosynchronous satellites for about $20 USD. It’s difficult to overstate the impact this has had on the world of radio hacking. It used to be only the Wizened Ham Graybeards could command the airwaves from the front panels of their $1K+ radios, but now even those who identify as software hackers can get their foot in the door for a little more than the cost of a pizza.

But as many new SDR explorers find out, having a receiver is only half the battle: you need an antenna as well. A length of wire stuck in the antenna jack of your SDR will let you pick up some low hanging fruit, but if you’re looking to extend your range or get into the higher frequencies, your antenna needs to be carefully designed and constructed. But as [Akos Czermann] shows on his blog, that doesn’t mean it has to be expensive. He shows how you can construct a very capable ADS-B antenna out of little more than an empty soda can and a bit of wire.

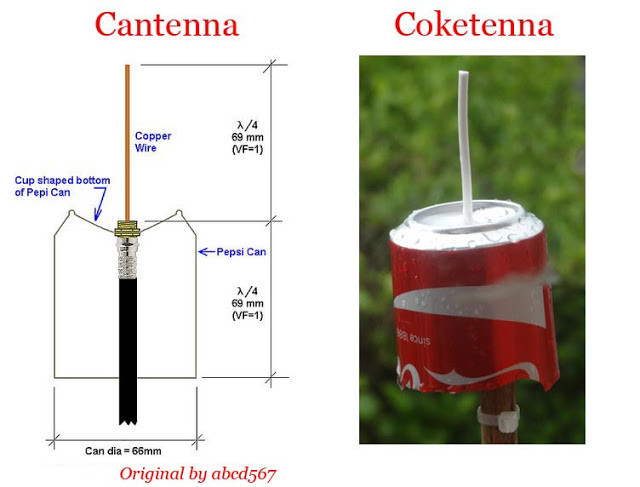

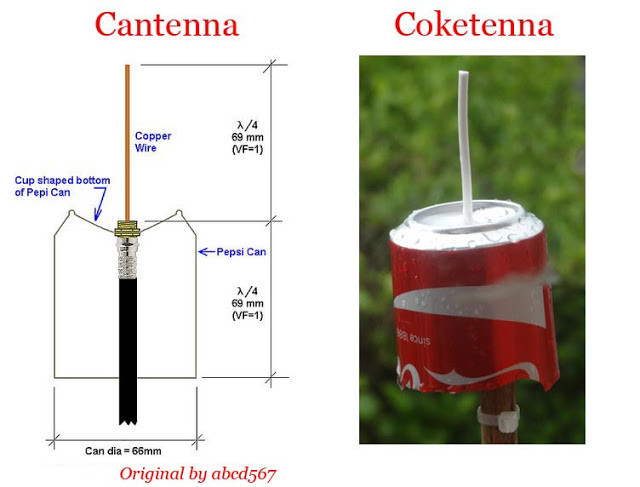

He makes it clear that the idea of using an old soda can as an antenna is not new, another radio hacker who goes by the handle [abcd567] popularized their own version of the “cantenna” some time ago. But [Akos] has made some tweaks to the design to drive the bar even lower, which he has dubbed the “coketenna”.

He makes it clear that the idea of using an old soda can as an antenna is not new, another radio hacker who goes by the handle [abcd567] popularized their own version of the “cantenna” some time ago. But [Akos] has made some tweaks to the design to drive the bar even lower, which he has dubbed the “coketenna”.

The primary advantages of his design is that you no longer need to solder anything or even use any special connectors. In fact, you can assemble this antenna with nothing more than a pocket knife.

You start by cutting the can down to around 68 mm in length, and cutting an “X” into the bottom. Then strip a piece of coax, and push it through the X. The plastic-coated center conductor of the coax should emerge through the bottom of the can, while the braided copper insulation will bunch up on the other side. If you want to make it really fancy, [Akos] suggests cutting a plastic drink bottle in half and using that as a cover to keep water out of the “coketenna”.

How well does it work? He reports performance being very similar to his commercial ADS-B antenna which set him back $45 USD. Not bad for some parts of out the trash.

We’ve covered the math of creating an ADS-B antenna in the past if you’d like to know more about the science of how it all works. But if you just want an easy way of picking up some signals, this “coketenna” and an RTL-SDR dongle will get you started in no time.

A delightful version of a clever one-dimensional game has been made by [Critters] which he calls

A delightful version of a clever one-dimensional game has been made by [Critters] which he calls