Whether you’re a programmer, gamer, writer, or data entry specialist, the keyboard is an extension of your nervous system. It’s not so much a tool as it is a medium for flow — for being in the zone. So I think it’s only natural that you should care deeply about your keyboard — how it looks, how it sounds, and above all, how it feels to finger-punch those helmeted little switches all the live-long day. That’s my excuse, anyway.

It might surprise you that mechanical keyboard switches can be modified in a number of ways. Depending on what you want from your keyboarding experience, you can make switches feel lighter or less scratchy, quiet them down, or tighten up any wobble in the housing. Why would you want to do this? Because customization is fun. Because electromechanical things are awesome, and because it’s fun to take switches apart and put them back together again. Because it’s literally hacking and this is Hackaday.

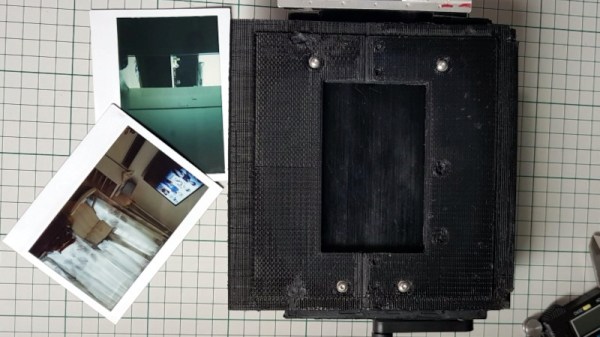

I got into switch modding because I wanted to put Cherry clears in my dactyl, but worried that they would take too much force to actuate and wear my fingers out. So I bought some really light (39g) springs and was really looking forward to swapping them into the clears, but they just don’t work. Like, physically. Slider goes down, slider gets stuck. It will come back up, but only if I hit it again and smear my finger to the side a bit at the same time. Those springs must be too weak to return clear sliders.

I took this as a sign that I should suck it up and use browns instead. After all, no one else has to know what my sliders look like. While I was opening switches, I tried out one of these super-light springs in a brown, thinking maybe they wouldn’t have to go to waste. Not only did the lighter spring work in the brown, it felt pretty nice. It’s hard to imagine how a whole keeb would feel based on a single switch, but if you can gather a handful and snap them into a plate to riffle your fingers over them, well, it’s probably close enough to a full keyboard to get a good feel for whatever mod you’re doing.