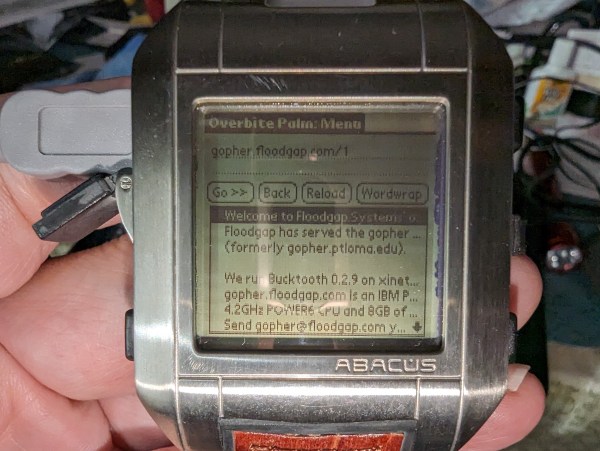

Like many new technologies, smartwatches needed a few iterations before they became useful enough for the average person. Early examples were too clunky and limited to be of use to anyone but geeks who wanted to show off their “next big thing”. The 2005 Fossil Wrist PDA was a prime example: although impressively compact for its time, its limited battery life and poor feature set made it obsolete as soon as it was released. But since it ran on Palm OS, it offered plenty of opportunity for hacking: Palm expert [Cameron Kaiser] has upgraded his Wrist with internet access.

While Palm OS 4 natively supports TCP/IP networking, this component was deleted from the Wrist version to save memory. In any case, the only viable network interface would have been the USB port, which isn’t too convenient for a watch. Not to be deterred, [Cameron] worked out a way to add network support back into the Wrist: he used the IR port on a Palm m505 to send a copy of its own network drivers to the watch. This works because both devices run the same basic OS version on the same CPU type; the only drawback is that the network setup dialog doesn’t respond correctly to the Wrist’s different set of buttons. Continue reading “Mobile Gopher Client Brings Fossil Wrist PDA Online”