Treat dispensers are old hat around here, but what if kitty doesn’t need the extra calories — and actually needs to drop some pounds? [MethodicalMaker] decided to link the treat dispenser to a cat wheel, and reward kitty for healthy behaviors. The dispenser can be programmed to make the cat run long enough to burn the calories of its treat. Over time, kitty can be trained to run longer between treats to really melt off the pounds.

The wheel itself is an off the shelf model called “One Fast Cat”; apparently these are quite cheap second hand as most cats don’t really see the point in exercise. [MethodicalMaker] glued evenly-spaced magnets along the rim in order to track the rotation with a hall effect sensor. A microcontroller is watching said sensor, and is programmed to release the treats after counting off a set number of revolutions. Control over the running distance and manual treat extrusion is via web portal, but the networking code had difficulty on the Arduino R4 [MethodicalMaker] started with, so he switched to an ESP32 to get it working.

The wheel itself is an off the shelf model called “One Fast Cat”; apparently these are quite cheap second hand as most cats don’t really see the point in exercise. [MethodicalMaker] glued evenly-spaced magnets along the rim in order to track the rotation with a hall effect sensor. A microcontroller is watching said sensor, and is programmed to release the treats after counting off a set number of revolutions. Control over the running distance and manual treat extrusion is via web portal, but the networking code had difficulty on the Arduino R4 [MethodicalMaker] started with, so he switched to an ESP32 to get it working.

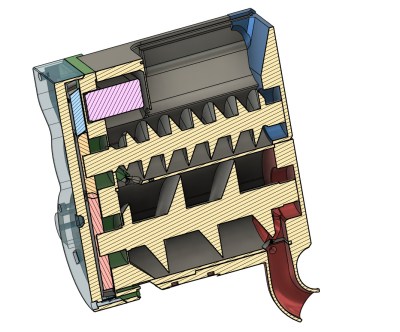

The real interesting part of this project is the physical design of the treat dispenser: it uses a double-auger setup to precisely control treat release. The first auger lives inside a hopper that holds a great many treats, but it tended to over-dispense so [MethodicalMaker] methodically made a second auger that sits beneath the hopper. The handful of treats extruded by the first auger are dispensed individually by the second auger, aided by a photosensor inside the exit chute to count treats. This also lets the machine signal when it needs refilling. For precise control, continuous servos are used to drive the augers. Aside from the electronics, everything is 3D printed; the STLs are on Printables, and the code is on GitHub.

If you don’t have a cat wheel, DIY is an option. If you don’t have a cat, we’ve also highlighted dog treat dispensers. If you don’t have either, check with your local animal shelter; we bet good money there are oodles ready to adopt in your town, and then you’ll have an excuse to enter one of your projects into our ongoing Pet Hacks Contest.

Continue reading “2025 Pet Hacks Contest: Automatic Treat Dispenser Makes Kitty Work For It”