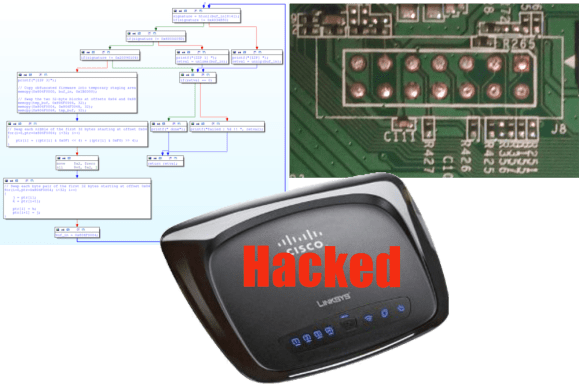

[Craig Heffner] has been busy with his Linksys WRT120N router. When we last checked in on [Craig] he had reverse engineered the obfuscation techniques used in the router’s firmware. Since then, he’s re-enabled JTAG, cracked the “encryption” used for saving configuration backups, and now he’s devised a simple attack to change the admin password. With the firmware unlocked, [Craig] went after the hardware JTAG. His first hurdle was a missing jumper connecting the TDI pin to the processor. With a solder blob making the connection, he then found the router would connect to his JTAG debugger, and immediately reset. TDI had been re-used as a GPIO in software, and assigned to the reset button on the back of the router. [Craig’s] JTAG pod was pulling the pin low and causing the reset. To make matters worse, the bootloader also redefined and checked for the reset button. If the button were pressed it would boot into a recovery mode. [Craig] patched the bootloader with a little help from IDA pro. He then desoldered the router’s flash and programmed it outside the system. The firmware required a similar patch. Rather than desolder the flash chip again, [Craig] created a firmware update the router would accept and flashed it via the router’s web interface.

Since he already was deep into the Linksys Firmware, [Craig] looked for any obvious attack vectors. He found a big one in the /cgi/tmUnBlock.cgi. Inside the firmware, the URL sent to the CGI would be sent through sprintf(). In plain english, it means that no input length checking was happening – so a URL longer than the firmware engineers expected (in this case 256 bytes) would overflow into areas of memory it wasn’t supposed to – in this case, the stack. For an astute attacker, that’s a wide open door. [Craig] was able to use find some Return Oriented Programming (ROP) gadgets and created an input value that would cause the router to reset its own administrator password. After running the exploit, a quick trip to the router’s webpage proved his attack was successful.

If that wasn’t enough, [Craig] also spent some time looking at the patches to the router’s firmware. The release notes of one of the patches mentioned encrypting configuration files. The WRT120N, like many routers, allows the owner to download and save the configuration as a file. It turned out that the “encryption” scheme was nothing more than an exclusive OR with 0xFF. A pretty weak encryption scheme by any standards. To [Craig] we send our congratulations. To the WRT120N software engineers, we’d suggest taking one of [Craig’s] embedded device exploitation classes.