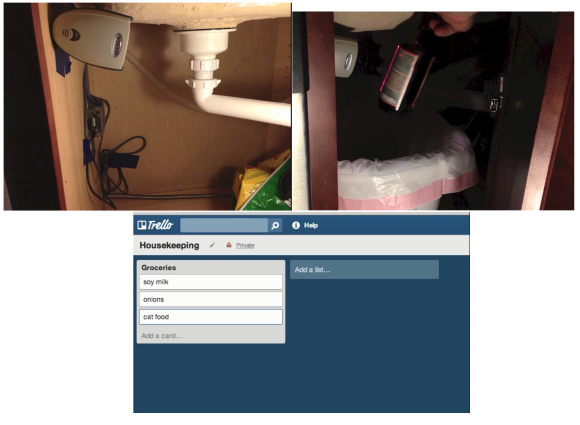

[Dan] has come up with a novel solution to the age old problem of keeping your grocery list up to date. He’s added a bar code scanner and a Raspberry Pi under a kitchen cabinet. He calls the system “Oscar”, though we don’t see any grouchiness in his trash can. When [Dan] runs out of a product, he simply throws it away. Just above his garbage and recycling bin is a low cost barcode scanner. [Dan] holds the item until the scanner reads, then sends it on it’s way to recycling or the landfill. The decoded bar code is processed by a Raspberry Pi also hiding under the cabinet. The Raspberry Pi sends the data to Trello.comusing the Trello api.

If a product isn’t recognized by Trello’s database, trello dispatches a text message to [Dan’s] phone. He can then add the product information via a web interface. We think the user interface is what’s great here. Once products are in the database, the only thing that has to be done day to day is pause for a moment before throwing a package away. [Dan] has all his code up on github, and has also created a reddit thread for Oscar.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9_MNOOgFDg4

[via reddit.com]