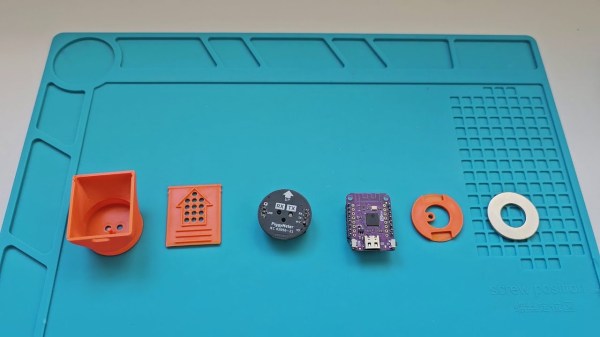

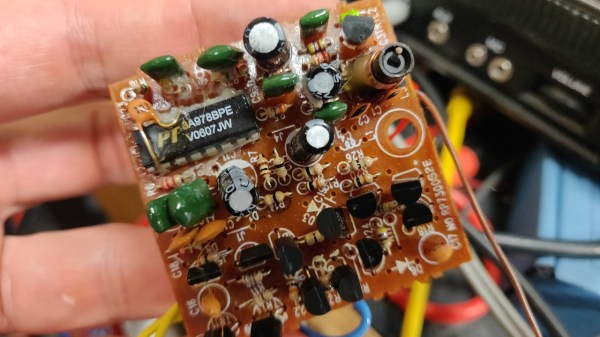

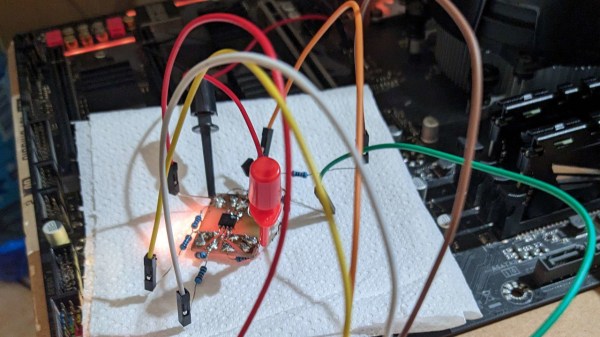

Last summer, I was hanging out with a friend from Netherlands for a week, and in the middle of that week, we decided to go on a 20 km bike trip to a nearby beach. Problem? We wanted to chat throughout the trip, but the wind noise was loud, and screaming at each other while cycling wouldn’t have been fun. I had some walkie-talkie software in mind, but only a single battery-powered Pi in my possession. So, I went into my workshop room, and half an hour later, walked out with a Pi Zero wrapped in a few cables.

I wish I could tell you that it worked out wonders. The Zero didn’t have enough CPU power, I only had single-core ones spare, and the software I had in mind would start to badly stutter every time we tried to run it in bidirectional mode. But the battery power solution was fantastic. If you need your hack to go mobile, read on.

Continue reading “Lithium-Ion Batteries Power Your Devboards Easily”