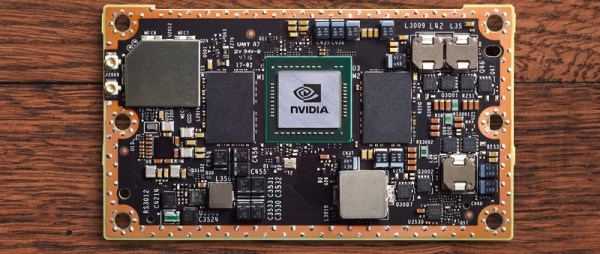

The last year has been great for Nvidia hardware. Nvidia released a graphics card using the Pascal architecture, 1080s are heating up server rooms the world over, and now Nvidia is making yet another move at high-performance, low-power computing. Today, Nvidia announced the Jetson TX2, a credit-card sized module that brings deep learning to the embedded world.

The Jetson TX2 is the follow up to the Jetson TX1. We took a look at it when it was released at the end of 2015, and the feelings were positive with a few caveats. The TX1 is still a very fast, very capable, very low power ARM device that runs Linux. It’s low power, too. The case Nvidia was trying to make for the TX1 wasn’t well communicated, though. This is ultimately a device you attach several cameras to and run OpenCV. This is a machine learning module. Now it appears Nvidia has the sales pitch for their embedded platform down.

Continue reading “Nvidia Announces Jetson TX2 High Performance Embedded Module”