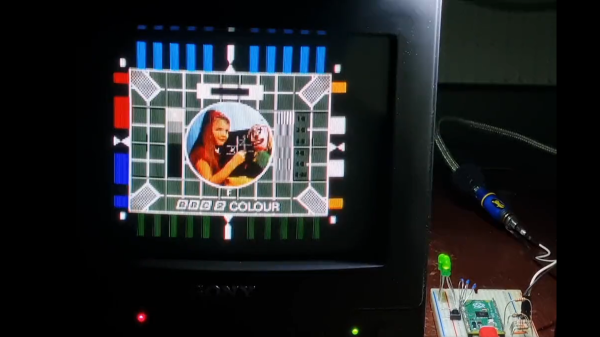

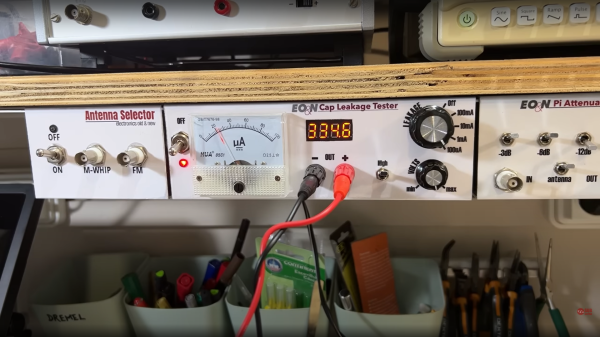

[Tom Verbeure] recently found himself lamenting the need to take screen grabs from an Advantest R3273 spectrum analyzer with a phone camera, as the older gear requires you to either grab tables of data over an expensive GPIB interface card, or print them to paper. Then he realized, why not make a simple printer port add-on that looks like a printer, but sends the data over USB as a serial stream?

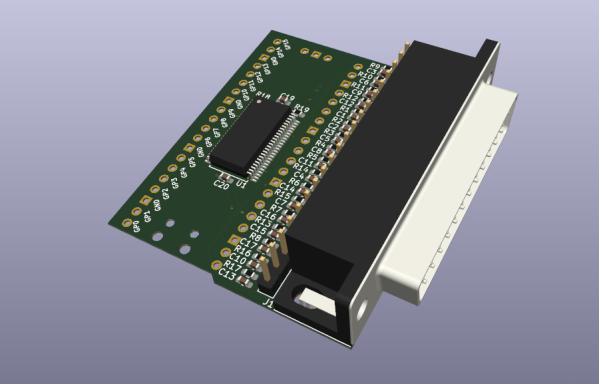

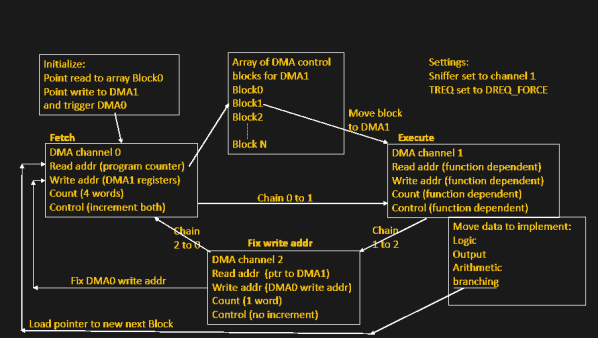

On the hardware side, the custom PCB (KiCAD project) is based on the Raspberry Pi Pico. Obvious form factor issues aside ([Tom] did revise the PCB to make it smaller) this is a shrewd move, as this is not a critical-path gadget so using the Pico as a USB-to-thing solution is a cost-effective way to get something working with minimal risk. One interesting design point was the use of the 74LVC161284 special function bus interface that handles the 5 V tolerance that the RP2040 lacks, whilst making the project compliant with IEEE-1284 — useful for the fussier instruments.

Using the service manual of the Sharp AP-PK11 copier/printer as a reference, [Tom] again, shows how to correctly use the chip, minimizing the design effort and scope for error. The complete project, with preliminary firmware and everything needed to build this thing, can be found on the project GitHub page. [Tom] does add a warning however that this project is still being worked on so adopters might wish to bear that in mind.

If you don’t own such fancy bench instrumentation, but grabbing screenshots from devices that don’t normally support it, is more your thing, then how about a tool to grab Game Boy screenshots?