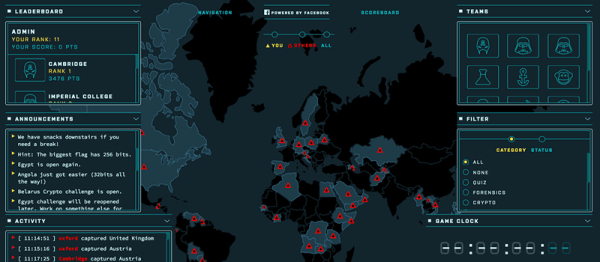

If you want to learn how to defeat computer security, nothing beats hands-on experience. Of course, if you get your hands on someone’s system without their permission, you may end up having a very short training that ends with a jail term. And that’s where capture-the-flag (CTF) events come in.

A CTF is a system of increasingly-difficult challenges that can’t be too easy or too hard. A well-designed CTF teaches all of the participants stuff that they didn’t know, no matter how far they get and what skills they came in with. Designing a good CTF is difficult.

But since it’s also a competition, running one also involves a lot of horrible bookkeeping for the folks running it. Registering teams and providing login pages is the dirty work that you have to do in the background, that takes away time from building the systems which others are going to take apart.

Which is why it’s great that Facebook is opening up their CTF-hosting platform, along with a few starter challenges, for us all to play along. We love CTFs and related hacking challenges. If this spurs the creation of more, we’re all for it. You can find the whole setup on GitHub.

If you’re new to CTFs, here’s an awesome collection of CTF-related material on GitHub to get you started. And if your tastes run more toward hardware hacking, we’ve covered previous firmware CTFs, but frankly there’s a lot more material out there. We feel a feature post coming on…

Thanks [ag4ve] for the unintentional tip!

Building a robot can be very simple — assembling pre-configured parts or building something small, quick, and cute — or it can be an endeavour that takes years of sweat and tears. Either way, the skills involved in building the ‘bot aren’t necessarily the same as those it takes to program the firmware that drives it, and then eventually the higher-level software that makes it functional and easy to drive.

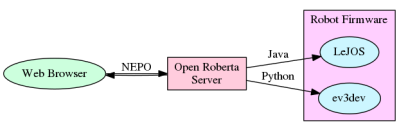

Building a robot can be very simple — assembling pre-configured parts or building something small, quick, and cute — or it can be an endeavour that takes years of sweat and tears. Either way, the skills involved in building the ‘bot aren’t necessarily the same as those it takes to program the firmware that drives it, and then eventually the higher-level software that makes it functional and easy to drive. Open Roberta is the user-facing middleware in a chain of software and firmware bits that make a robot work in a classroom environment. For the students, everything runs inside a browser. OR provides a webserver, robot programming interface and language, and then converts the output of the students’ programs to something that can be used with the robots’ firmware. The robots that are used in classrooms are mostly based on the Lego Mindstorms EV3 platform because it’s easy to put something together in short order. (But if you don’t have an EV3, don’t despair and read on!)

Open Roberta is the user-facing middleware in a chain of software and firmware bits that make a robot work in a classroom environment. For the students, everything runs inside a browser. OR provides a webserver, robot programming interface and language, and then converts the output of the students’ programs to something that can be used with the robots’ firmware. The robots that are used in classrooms are mostly based on the Lego Mindstorms EV3 platform because it’s easy to put something together in short order. (But if you don’t have an EV3, don’t despair and read on!)