Who wouldn’t want an autonomous drone to deliver cans of fizzy drink fresh from the fridge? [Alex Toussaint] did, and in thinking how such a machine might work he embarked on a path that eventually led him to create a fully functional ultrasonic 3D scanner. In writing it up he’s produced a straightforward description of how the system works, which should also be of interest to anyone curious about phased array radar. He starts with an easy-to-understand explanation of the principle behind phased array beam forming, and there follows his journey into electronics as he uses this ambitious project to learn the art from scratch. That he succeeded is testament to his ability as well as his sheer tenacity.

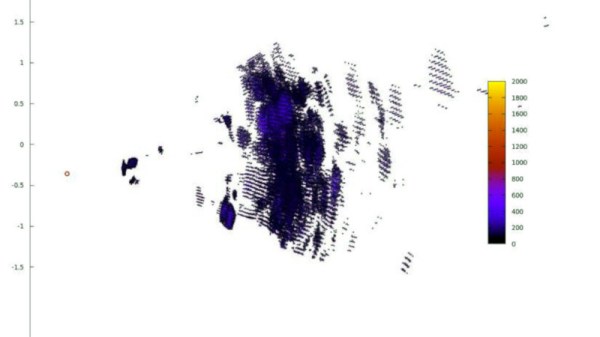

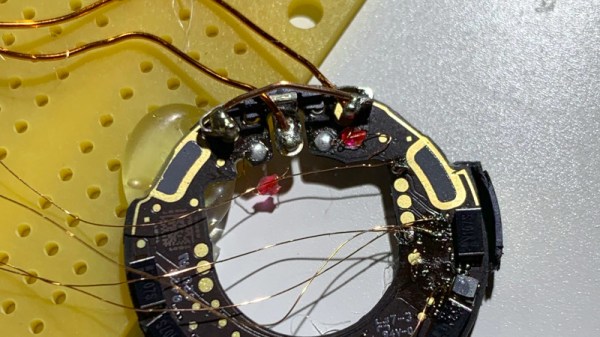

He finally arrived at a grid of 100 ultrasonic emitters controlled from an Arduino through a series of shift register boards. Using this he can steer his ultrasonic beam horizontally as well as vertically, and receive echoes from objects in three-dimensional space. The ornamental bird example he uses for his scanning tests doesn’t quite emerge in startling clarity, but it is still clear that an object of its size and rough shape is visible enough for the drone in his original idea to detect it. If you would like to experiment with the same techniques and array then all the resources can be found in a GitHub repository, meanwhile we’re still impressed with the progress from relative electronics novice to this. We hope the ideas within it will be developed further.

He finally arrived at a grid of 100 ultrasonic emitters controlled from an Arduino through a series of shift register boards. Using this he can steer his ultrasonic beam horizontally as well as vertically, and receive echoes from objects in three-dimensional space. The ornamental bird example he uses for his scanning tests doesn’t quite emerge in startling clarity, but it is still clear that an object of its size and rough shape is visible enough for the drone in his original idea to detect it. If you would like to experiment with the same techniques and array then all the resources can be found in a GitHub repository, meanwhile we’re still impressed with the progress from relative electronics novice to this. We hope the ideas within it will be developed further.

We’ve seen ultrasonic arrays before, but mainly used in levitation experiments.