An inexorable trend over the last decade or more has been the exodus of AM radio stations from the low frequency and HF broadcast bands. The bandwidth and thus audio quality at these frequencies puts them at a disadvantage against FM and internet streamed services, and the long-distance advantage of HF has been reduced by easy online access to overseas content. The world has largely moved on from these early-20th-century technologies, leaving them ever more a niche service.

Happily for medium- and long-wave enthusiasts there is a solution to their decline, in the form of DRM, or Digital Radio Mondiale, a digital scheme that delivers cleaner audio and a range of other services in the same space as a standard-sized AM channel. DRM receivers are somewhat rare and usually not cheap though, so news of an Android app DRM receiver from Starwaves is very interesting indeed.

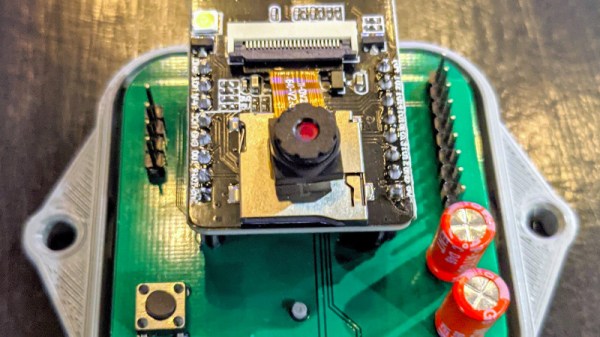

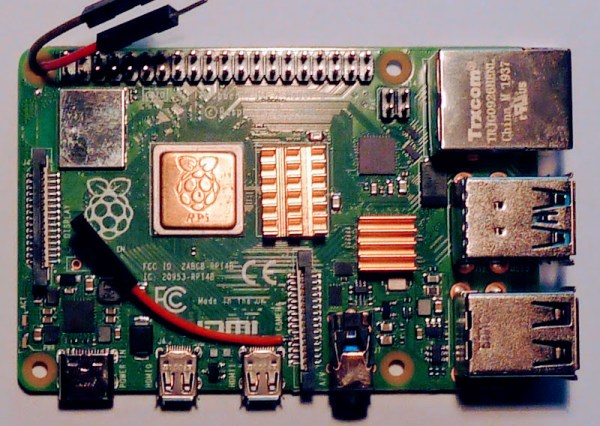

DRM uses a licensed encoding scheme from the Fraunhofer Institute, and this product follows on from a line of hardware DRM receivers that Starwave have developed using their technology. It uses the Android device as a front-end for any of a number of SDR receivers, including the popular RTL-SDR series. It supports the VHF variant of DRM, though we’re guessing that since the best chance of finding a DRM channel for experimentation is on HF that an RTL-SDR with the HF modification will be required. We think it’s an interesting development because the growth of DRM is a chicken-and-egg situation where there must be enough receivers in the wild for broadcasters to consider it viable.