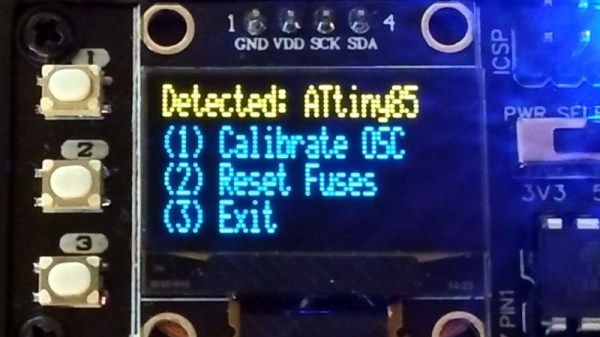

In an age of streaming media it’s easy to forget the audio CD, but they still remain as a physical format from the days when the “Play” button was not yet the “Pay” button. A CD player may no longer be the prized possession it once was, but it’s still possible to dabble in the world of 120 mm polycarbonate discs if you have a fancy for it. It’s something [Daniel1111] has done with his Arduino CD player, which uses the little microcontroller board to control a CD-ROM drive via its IDE bus.

The project draws heavily from the work of previous experimenters, notably ATAPIDUINO, but it extends them by taking its audio from the drive’s S/PDIF output. A port expander drives the IDE interface, while a Cirrus Logic WM8805 S/PDIF transceiver handles the digital audio and converts it to an I2S stream. That in turn is fed to a Texas Instruments PCM5102 DAC, which provides a line-level audio output. All the code and schematic can be found in a GitHub repository.

To anyone who worked in the CD-ROM business back in the 1990s this project presses quite a few buttons, though perhaps not enough to dig out all those CDs again. It would be interesting to see whether the I2S stream could be lifted from inside the drive directly, or even if the audio data could be received via the IDE bus. If you’d like to know a bit more about I2S , we have an article for you.