Despite widespread pandemic cancellations, BornHack still happened this year and they even managed to once again bring an electronic badge to all attendees. If you missed it, I’ve already published an overview of the hacker camp itself. Today let’s dig into the 2020 BornHack badge!

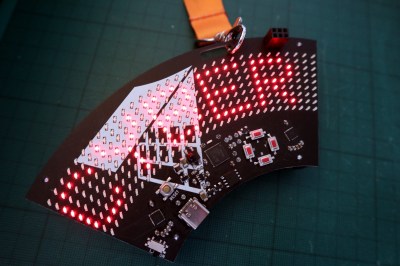

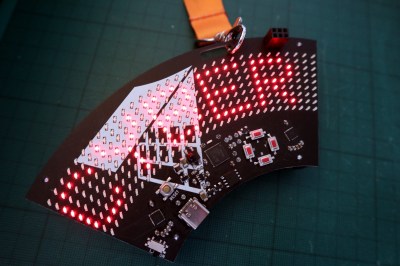

Designed by Thomas Flummer and manufactured in Denmark, it takes the form of a PCB in the shape of a roughly 60 degree circular arc with most of its top side taken up by a 9 by 32 array of SMD LEDs. There is the usual 4-way button array and space for an SAO connector on the rest of the front face, while on the rear are a set of GPIO pads and a pair of AA battery holders for power. Connectivity is via USB-C and infra-red, and usefully there is also a power on/off switch.

At the heart of its hardware is a SAMD21G18A ARM Cortex M0+ microcontroller which is perhaps not the most exciting of chips, but the hardware becomes more interesting with the LED drivers. A pair of the IS31FL3731 chips (you may recognise from Brian Benchoff’s Mr. Robot badge) each drive half of the Charliplexed LED array. These versatile chips take the bother of scanning the LED matrix away from the microcontroller with their own internal frame registers fed from an I2C interface. This choice both makes the best use of the relatively meagre microcontroller in this application, and opens the way for the software choice. This badge runs Adafruit’s CircuitPython, and can thus be programmed over the USB connection in the same way as any other CircuitPython board. To test this I put aside my GNU/Linux laptop, and picked up something considerably less versatile to test its ease of use: a Chromebook.

At the heart of its hardware is a SAMD21G18A ARM Cortex M0+ microcontroller which is perhaps not the most exciting of chips, but the hardware becomes more interesting with the LED drivers. A pair of the IS31FL3731 chips (you may recognise from Brian Benchoff’s Mr. Robot badge) each drive half of the Charliplexed LED array. These versatile chips take the bother of scanning the LED matrix away from the microcontroller with their own internal frame registers fed from an I2C interface. This choice both makes the best use of the relatively meagre microcontroller in this application, and opens the way for the software choice. This badge runs Adafruit’s CircuitPython, and can thus be programmed over the USB connection in the same way as any other CircuitPython board. To test this I put aside my GNU/Linux laptop, and picked up something considerably less versatile to test its ease of use: a Chromebook.

# configure I2C

i2c = busio.I2C(board.SCL, board.SDA)

# turn on LED drivers

sdb = DigitalInOut(board.SDB)

sdb.direction = Direction.OUTPUT

sdb.value = True

# set up the two LED drivers

display = adafruit_is31fl3731.Matrix(i2c, address=0x74)

display2 = adafruit_is31fl3731.Matrix(i2c, address=0x77)

text_to_show = "BornHack 2020 - make clean"

CircuitPython devices mount as a disk drive in which can be found a Python file that can be edited with the code of your choice. The BornHack badge ships with code to display a BornHack banner text, which serves as a quick introduction to the capabilities of its display. It’s noticeable that the text scrolling performance leaves something to be desired, but this microcontroller is hardly one of the more powerful supported by the CircuitPython platform. The Chromebook was happily able to edit the code, though viewing the Python serial console necessitated diving into its Linux virtual machine.

The BornHack badge then, an attractive design that fulfils the aim of being capable and easy to program through its use of the popular CircuitPython platform, and through its decent sized LED matrix and available GPIOs with the chance of seeing a use beyond the camp as a general purpose display/experimentation platform. It may not be the most powerful of badges, but it does its job well. In particular it has achieved the feat missed by so many others, of arriving at the camp fully assembled and with working hardware and software. You can see more about it in Thomas’ badge presentation at the camp (cut from a stream, talk begins at 5:27) which we’ve placed below the break.

We look forward to seeing its influence upon other similar badges. Meanwhile if you are interested, you can compare it with the 2019 BornHack badge which we reviewed last year.

Continue reading “Hands-On: BornHack 2020 Badge Has 9×32 Of Bling Fed By CircuitPython” →

At the heart of its hardware is a

At the heart of its hardware is a