A distance record for LoRa transmission has been set that you probably won’t be able to beat. Pack up your gear and go home, nothing more to achieve here. At a superficial reading having a figure of 71,572 km (44,473 miles) seems an impossible figure for one of the little LoRa radio modules many of us have hooked up to our microcontrollers, but the story isn’t quite what you’d expect and contains within it some extremely interesting use of technology.

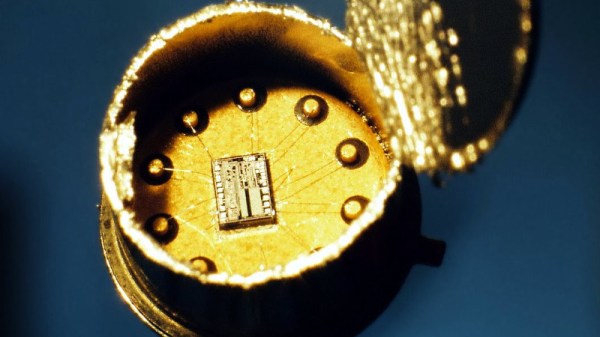

So the folks at Outernet have sent data over LoRa for that incredible distance, but they did so not through the little ISM band modules we’re used to but over a suitably powerful Ku-band uplink to a geostationary satellite. They are also not using the LoRaWAN protocols of the earthbound systems, but simply the LoRa modulation scheme. So it’s not directly comparable to terrestrial records such as the 702 km we reported on last year, and they are the first to admit that.

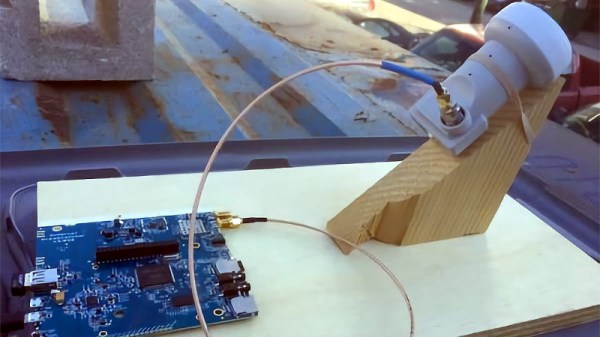

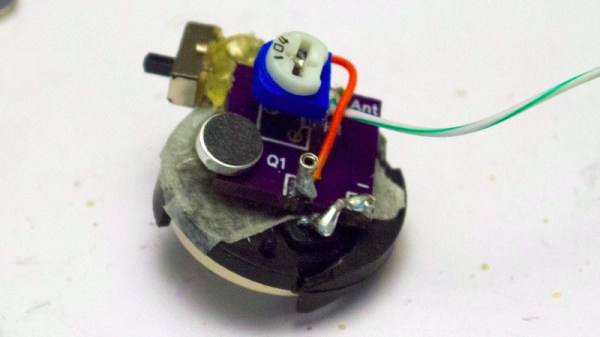

Where their achievement becomes especially interesting though is in their choice of receiver. We are all used to Ku-band receivers, you may even have one on your house somewhere for satellite TV. It will probably involve a parabolic dish with a narrow beam width and an LNB whose horn antenna is placed at its focus. It would have required some skill and effort to set up, because it has to be pointed very carefully at the satellite’s position in the sky. Outernet’s mission of delivering an information service with the lowest possible barrier to entry precludes the extra expense of shipping a dish and providing trained staff to align it, so they take a very different approach. Their receiver uses either an LNB horn or a small patch antenna pointing at the satellite, with none of the dishes or phased arrays you might be used to in a Ku-band installation.

You might wonder how such a receiver could possibly work with such a meagre antenna, but the secret lies in LoRa’s relatively tiny bandwidth as well as the resistance to co-channel interference that is a built-in feature of the LoRa modulation scheme. Even though the receiver will be illuminated by multiple satellites at once it is able to retrieve the signal and achieve a 30 kb/s data rate that they hope with technical refinements to increase to 100 kb/s. This rate will be enough over which to push an SD video stream to name just one of the several examples of the type of content they hope to deliver.

It’s likely that the average Hackaday reader will not be hiring satellite uplink time upon which to place their LoRa traffic. But this story does provide a demonstration of LoRa’s impressive capabilities, and will make us look upon our humble LNBs with new eyes.

Via ABOpen.