Many of us will have at some time over the last couple of years bought a LoRaWAN module or two to evaluate the low power freely accessible wireless networking technology. Some have produced exciting and innovative projects using them while maybe the rest of us still have them on our benches as reminders of projects half-completed.

If your LoRaWAN deployment made it on-air, you’ll be familiar with the range that can be expected. A mile or two with little omnidirectional antennas if you are lucky. A few more miles if you reach for something with a bit of directionality. Add some elevation, and range increases.

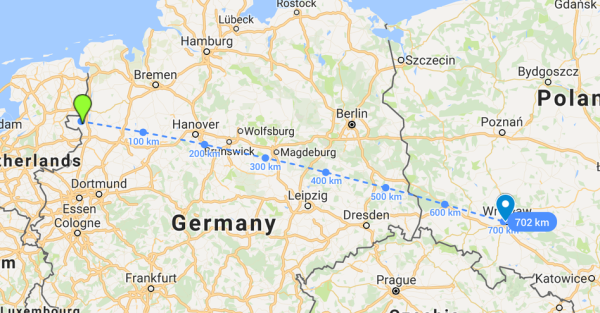

A couple of weeks ago at an alternative society festival in the Netherlands, a balloon was launched with a LoRaWAN payload on board that was later found to have made what is believed to be a new distance record for successful reception of a LoRaWAN packet. While the balloon was at an altitude of 38.772 km (about 127204.7 feet) somewhere close to the border between Germany and the Netherlands, it was spotted by a The Things Network node in Wroclaw, Poland, at a distance of 702.676km, or about 436 miles. The Things Network is an open source, community driven effort that has built a worldwide LoRaWAN network.

A couple of weeks ago at an alternative society festival in the Netherlands, a balloon was launched with a LoRaWAN payload on board that was later found to have made what is believed to be a new distance record for successful reception of a LoRaWAN packet. While the balloon was at an altitude of 38.772 km (about 127204.7 feet) somewhere close to the border between Germany and the Netherlands, it was spotted by a The Things Network node in Wroclaw, Poland, at a distance of 702.676km, or about 436 miles. The Things Network is an open source, community driven effort that has built a worldwide LoRaWAN network.

Of course, a free-space distance record for a balloon near the edge of space might sound very cool and all that, but it’s not going to be of much relevance when you are wrestling with the challenge of getting sensor data through suburbia. But it does provide an interesting demonstration of the capabilities of LoRaWAN over some other similar technologies, if a 25mW (14dBm) transmitter can successfully send a packet over that distance then perhaps it might be your best choice in the urban jungle.

If you’re curious about LoRaWAN, you might want to start closer to home and sniff for local activity.