The star turn of most hackspaces and other community workshops is usually a laser cutter. An expensive and fiddly device that it makes much more sense to own collectively than to buy yourself.

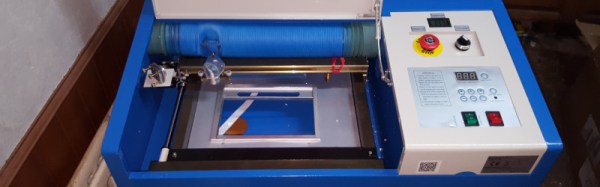

This isn’t to say that laser cutters are outside the budget of the experimenter though, we’re all familiar with the inexpensive table-top machines from China. Blue and white boxes that can be yours for a few hundred dollars, and hold the promise of a real laser cutter on your table.

Owning one of these machines is not always smooth sailing though, because their construction and choice of components are often highly variable. A thorough check and often a session of fixing the non-functional parts is a must before first power-on.

[Extreme Electronics] bought one, and in a series of posts documented the process from unboxing to cutting. Starting with a full description of the machine and what to watch for out of the box, then a look at the software. A plugin for Corel Draw was supplied, along with a dubious copy of Corel Draw itself. Finally we see the machine in operation, and the process of finding the proper height for beam focus by cutting an inclined plane of acrylic.

The series rounds off with a list of useful links, and should make interesting reading for anyone, whether they are in the market for a cutter or not.

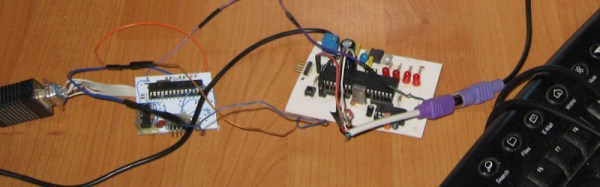

These cutters/engravers have featured here before many times. Among many others we’ve seen one working with the Mach3 CNC software, or another driven by a SmoothieBoard.