In 2013 the dean of an Ethiopian university addressed Maker Faire Hannover and outlined one of his concerns; that the high price of developed-world textbooks was holding back the cause of education for universities such as his own in developing countries. He was there to ask for help from the maker community to solve his problem, and a group of his audience took up the challenge to create an affordable and accessible automatic book scanner.

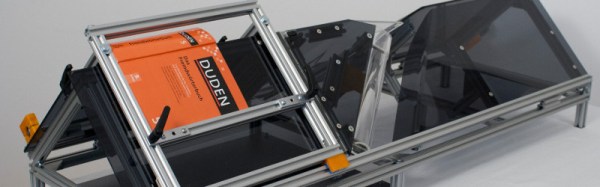

Their scanner builds on the work of Google engineer [Dany Qumsiyeh], whose open source linear book scanner turns pages by traversing the opened book over a triangular prismic former such that pages are turned by vacuum as they pass over carefully designed slots in its surface. Their modification replaces the vacuum with the Coandă effect, to more gently tease open each page and it is hoped reduce the chance of damaging the volumes being scanned.

The whole machine is controlled by a Raspberry Pi, and the scanning is performed by linear scanning optics, sensors, and electronics taken from flatbed scanners.

An important design goal of the project was to ensure that the scanner could be built without special tools or expertise that might be difficult to find in a developing country, as well as that it should be as inexpensive as possible. The frame of the machine is off-the-shelf extruded aluminium, and the body is acrylic sheet which can be cut to shape with a hand saw if necessary. It is estimated that the device will cost in the region of 500 Euros (about $568) to build.

More information can be found at the project’s web site (German language, Google translate link), including a selection of videos such as the one below the break showing the device in operation.

Writing from the perspective of having been peripherally involved in a professional book scanning operation at a large publisher the benefits of this machine are immediately apparent. Removing the binding and automatically scanning each page as an individual sheet produces a very fast and high quality result, but by its very nature damages the volume being scanned. This machine promises to deliver a solution to the problem of book scanning that is considerably less intrusive.

It is also worth noting that the project does not address any copyright issues that might arise from scanning commercially published textbooks, though this is more of a concern for the end user in terms of what they scan with it than it is for the maker.

Continue reading “Automatic Book Scanner To Bring Knowledge To Ethiopian Students” →