Debugging network issues isn’t easy; many a sysadmin has spent hours trying to figure out which of the many links between client and server is misbehaving. Having a few clear pointers helps: if you can show that the internet connection is up, that already narrows down the problem to either the server or, most likely, the client computer.

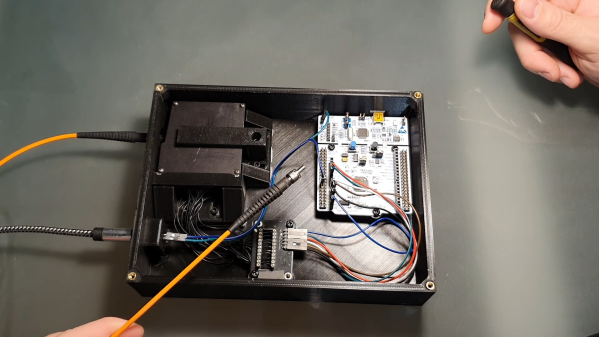

After hearing “is the internet up” one too many times, [whiskeytangohotel] decided to make a clearly visible indicator to show the status of the local uplink. He used his father’s old Simpson 260 VOM as a display, with its large analog indicator pointing at a steady value if the internet’s up, and wagging back and forth if there’s an outage. The exact value indicated is determined by the average ping time for a couple of different servers, so that you can also tell if the connection is slower than normal.

The ping times are measured by an ESP8266 connected to WiFi, which checks a predefined list of web servers and calculates the average ping time every fifteen seconds. An analog value in the 2.5 V range is then generated and measured by the meter. The smooth motion of an old analog meter stands in nice contrast to the modern-day problem of unstable WiFi.

While analog multimeters definitely have their uses, we’re the first to admit that our classic meters don’t see as much action as they could. Repurposing them as [whiskeytangohotel] did is a neat way of keeping those heirlooms around for the next generation. Of course, if you don’t have an analog multimeter, you could also use an analog clock for your ping meter. Continue reading “Classic Multimeter Tells You If Your WiFi’s Working”