Nine years ago, MakerBot was acquired by Stratasys in a deal worth slightly north of $600 million. At the time it was assumed that MakerBot’s line of relatively affordable desktop 3D printers would help Stratasys expand its reach into the hobbyist market, but in the end, the company all but disappeared from the hacker and maker scene. Not that many around these parts were sad to see them go — by abandoning the open source principles the company had been built on, MakerBot had already fallen out of the community’s favor by the time the buyout went through.

So today’s announcement that MakerBot and Ultimaker have agreed to merge into a new 3D printing company is a bit surprising, if for nothing else because it seemed MakerBot had transitioned into a so-called “zombie brand” some time ago. In a press conference this afternoon it was explained that the new company would actually be spun out of Stratasys, and though the American-Israeli manufacturer would still own a sizable chunk of the as of yet unnamed company, it would operate as its own independent entity.

In the press conference, MakerBot CEO Nadav Goshen and Ultimaker CEO Jürgen von Hollen explained that the plan was to maintain the company’s respective product lines, but at the same time, expand into what they referred to as an untapped “light industrial” market. By combining the technology and experience of their two companies, the merged entity would be uniquely positioned to deliver the high level of reliability and performance that customers would demand at what they estimated to be a $10,000 to $20,000 USD price point.

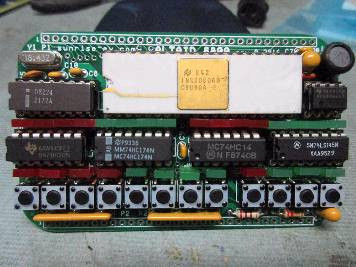

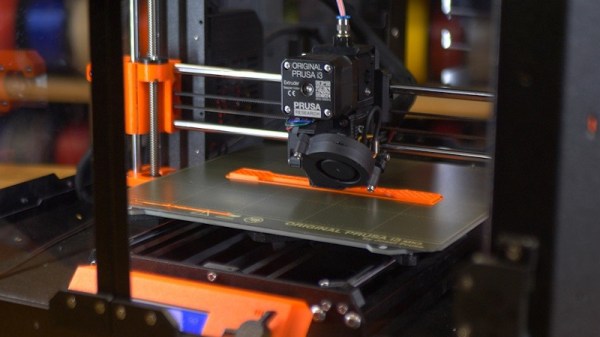

When MakerBot announced their new Method 3D printer would cost $6,500 back in 2018, it seemed clear they had their eyes on a different class of clientele. But now that the merged company is going to put their development efforts into machines with five-figure price tags, there’s no denying that the home-gamer market is officially in their rear-view mirror. That said, absolutely zero information was provided about the technology that would actually go into said printers, although given their combined commercial experience, it seems all but a given that these future machines will use some form of fused deposition modeling (FDM).

Now we’d hate to paint with too broad a brush, but we’re going to assume that the average Hackaday reader isn’t in the market for a 3D printer that costs as much as a decent used car. But there’s an excellent chance you’re interested in at least two properties that will fall under the umbrella of this new printing conglomerate: MakerBot’s Thingiverse, and Ultimaker’s Cura slicer. In the press conference it was made clear that everyone involved recognized both projects as vital outreach tools, and that part of the $62.4 million cash investment the new company is set to receive has been set aside specifically for their continued development and improvement.

We won’t beat around the bush — Thingiverse has been an embarrassment for years, even before they leaked the account information of a quarter million users because of their antiquated back-end. A modern 3D model repository run by a company the community doesn’t openly dislike has been on many a hacker’s wish list for some time now, but we’re not against seeing the service get turned around by a sudden influx of cash, either. We’d also be happy to see more funding go Cura’s way as well, so long as it’s not saddled with the kind of aggressive management that’s been giving Audacity users a headache. Here’s hoping the new company, whatever it ends up being called, doesn’t forget about the promises they’re making to the community — because we certainly won’t.