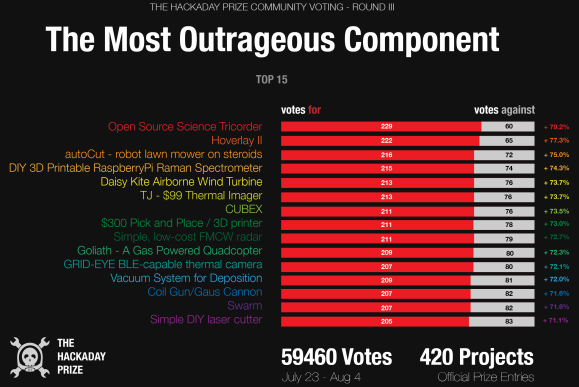

Round 3 of Community Voting has drawn to a close. This time around we had nearly 60,000 votes for 420 projects! The first voter lottery drawing didn’t turn up a winner, but on Friday we ended up giving away the bench supply. We’ll cover the projects with the top votes in just a moment, but first let’s take a look at the voter lottery prize for the new round.

You must vote at least once in this new round to be eligible for the voter lottery on Friday!

We’ve got so many prizes in the package for the fourth round of Astronaut or Not that we’re just showing you a few in this image.

On Friday morning we’ll be drawing a random number and checking it against the Hacker profiles on Hackaday.io. If that person has voted in this current round, they win. If not, they’ll be kicking themselves (emptyhandedly) for not taking part in the festivities.

This week’s prize package includes:

- Terasic Technologies DE0 Development Board for Cyclone III FPGA

- Raspberry Pi Model B+ Board

- Element14 BeagleBone Black

- MSP430F5529 USB LaunchPad Evaluation Kit

- SimpleLink Wi-Fi CC3200 LaunchPad

- AVRISP mkII Atmel Programmer

- PICkit 3 Microchip In-Circuit Debugger

- ST-LINK/V2 ST Microelectronics In-Circuit Debugger/Programmer

- B&K Precision 1550 Switching DC Bench Power Supply

- Fluke 115 Digital Multimeter

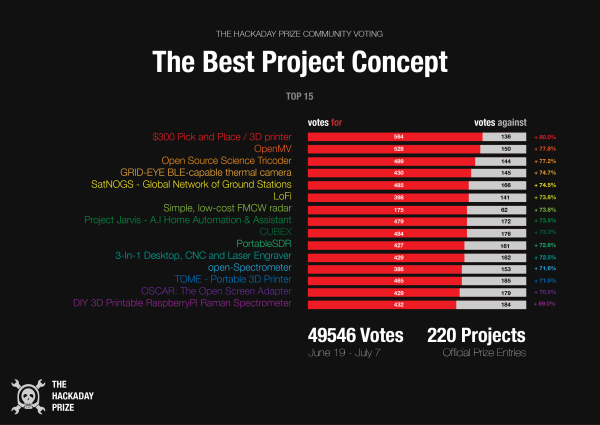

Now onto the results:

Continue reading “New Round Of Astronaut Or Not: Too Cool For Kickstarter”

Here’s an interesting thought: it’s possible to build a cubesat for perhaps ten thousand dollars, and hitch a ride on a launch for free thanks to a NASA outreach program. Tracking that satellite along its entire orbit would require dozens of ground stations, all equipped with antennas, USB TV tuners, and a connection to the Internet. It’s actually more expensive to build and launch a cubesat than it costs to build a network of ground stations to get reasonably real-time telemetry from a cubesat. The future is awesome and weird, it seems.

Here’s an interesting thought: it’s possible to build a cubesat for perhaps ten thousand dollars, and hitch a ride on a launch for free thanks to a NASA outreach program. Tracking that satellite along its entire orbit would require dozens of ground stations, all equipped with antennas, USB TV tuners, and a connection to the Internet. It’s actually more expensive to build and launch a cubesat than it costs to build a network of ground stations to get reasonably real-time telemetry from a cubesat. The future is awesome and weird, it seems.