What if you don’t put airfoils on a central, spinning axis, but instead have them careen around a circular track? If you’re a company called Airloom, you’d say that it’s a very cheap, very efficient and highly desirable way to install wind-based generators that can do away with those unsightly and massive 100+ meter tall wind turbines, whether on- or offshore. Although grand claims are made, and venture capital firms have poured in some money, hard data is tough to find on their exact design, or the operating details of their one and only claimed kW-level prototype.

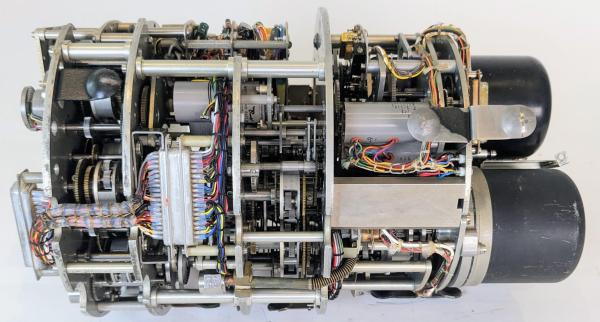

Despite the claims made by Airloom, they’re not the first to have this idea, with Transpower in the 1980s making itself famous with their ‘flying clothesline’ that featured a continuous loop of sails tensioned between two ropes. These ran around a pole on either end with each having a generator for a claimed total of 200 kW. Ultimately Transpower seems to have gone under along with many other wind power pioneers of the era as they couldn’t make their idea economically feasible. Something which is a definite trend in the field.

Some parts about Airloom’s design are definitely concerning, with the available images showing each airfoil running along a central rail on a number of wheels and with their ‘Power Takeoff’ (i.e. generator) not defined in any meaningful manner. Here is where [Robert Murray-Smith] had a bit of fun in a recent video, creating his own dual-chain version that somewhat resembles a mixture between the Transpower and Airloom designs. He also put the design up on Thingiverse for others to 3D print and tinker with, requiring a handful of bearings for smooth running.

For the power takeoff, [Robert] suggests that in his design the cogs around which the chain moves could be attached to a generator (like in the Transpower design), but he could see no indication of how Airloom intends to do this. Feel free to put your own speculations in the comments. And if you’re from Airloom, show us the details!

Continue reading “Airloom’s Whacky Wind Clothesline Turbine Idea”