Rocketry is an exacting science, involving a wide variety of disciplines, encompassing everything from fluid mechanics to thermodynamics and materials engineering. As complex as it sounds, that doesn’t mean it’s beyond the purview of the average maker. [Sciencish] demonstrates this with a series of experiments on rocket nozzles in the home lab. (Video, embedded below.)

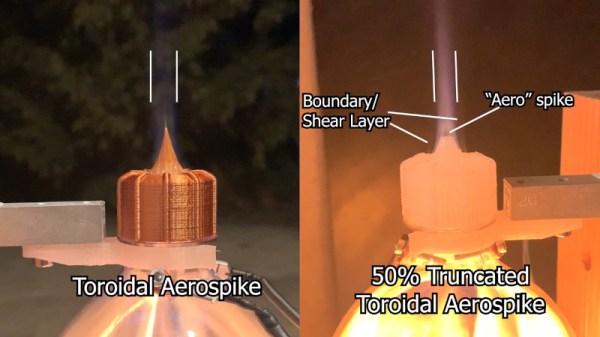

The video starts with an amusing analogy about nozzle design based on people fleeing a bad pizza. From there, [Sciencish] 3D prints a wide variety of nozzle designs for testing. The traditional bell nozzle is there, of course, along with the familiar toroidal and linear aerospikes and an expansion deflection design. Of course, 3D printing makes it easy to try out fun, oddball geometries, so there’s also a cowbell nozzle , along with the fancy looking square and triangular aerospikes too. Testing involves running the nozzles on a test stand instrumented with a load cell. A soda bottle is filled with rubbing alcohol vapour, and the mixture is ignited, with each nozzle graded on its thrust output. The rockets are later flown outside, reaching heights over 40 feet.

[Sciencish] notes that the results are a rough guide only, as the fuel/air mixture was poorly controlled. Despite this, it’s a great look at nozzle design and all the science involved. It also wouldn’t be too hard to introduce a little more rigour and get more accurate data, either. However, if solid fuels are more your jam, consider brewing up some rocket candy instead.

Continue reading “Experimenting With 3D Printed Rocket Nozzles”