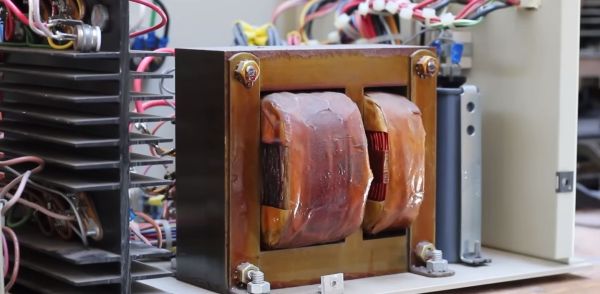

Laser printers today are cheap and readily available. But in 1976, they were the height of printing technology. The IBM 3800 was the $175,000 printer to have in that year. (Video, embedded below.) But you couldn’t have one on your desktop. Even if you could afford it, the thing is the size of a car, and we don’t even want to guess what it weighs. The printer took tractor-fed continuous form paper and could do 167 pages a minute at about 150 dots per inch (actually 180 x 144). For the record, that was as much as 1.7 miles of paper an hour!

In those days, people who would use this printer traditionally had massive banks of noisy impact printers. We imagine this device saved many data processing person’s hearing. Compared to a modern laser printer, though, it needed a lot of maintenance. For example, the initial models needed a xenon flash lamp replaced every month, although later models could go years on one bulb. Looking at some of the hardware in the video, it was probably made closer to the end of life for these printers which were made through 1999.

Continue reading “Retrotechtacular: The $175,000 Laser Printer”