Like most of us, [Hunter] and his partner [Katyrose] have been in quarantine for the past few months. Unlike most of us, they spun a 3D printed chicken playground design hackathon out of their self-isolation. The idea is simple: to build a playground full of toys custom-tailored to appease each chicken’s distinctive taste. The execution, however, can be proven a little tricky given that chickens are very unpredictable.

For each of the four select chickens in their coop, the couple designed separate toys based on their perceived interests. One, showing a fondness for worms, inspired the construction of a tree adorned with rice noodles in place of the living article, and moss to top it off. For late-night entertainment, the tree is printed in glow-in-the-dark filament. The others were presented with a print-in-place rotating mirror disguised as a flower, and a pecking post covered in peanut butter and corn. As a finishing piece, the fourth toy is designed as a jungle gym post with a reward of bread at the top for the chicken who dares climb it. Since none of the chickens seemed interested in it, they were eventually hand-fed the bread.

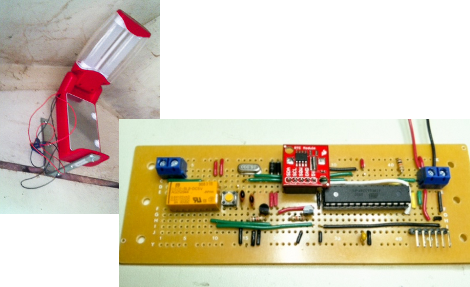

With no other entries to their hackathon, [Hunter] declared themselves as the winners. The 3D files for their designs are available for their patrons to print, should they have their own chicken coops they want to adorn. While the hackathon might’ve been a success for them, their chickens in particular seemed unimpressed with their new toys, only going to show that the only difference between science and messing around is writing it down, or in this case, filming the process. If you’re looking for other ways to integrate your chickens into the maker world, check out this Twitch-enabled chicken feeder, or this home automation IoT chicken coop door. Meanwhile, check out the video about their findings after the break.

Continue reading “Appeasing Chicken Tastes With 3D Printing”