The floppy disk is a technology that is known only to the youth of today as the inspiration for the Save icon. There’s a lot of retro computing history tied up in these fragile platters, thus preservation is key. But how to go about it? [CHZ-Soft] has found an easy way, using a logic analyzer and a healthy dose of Python.

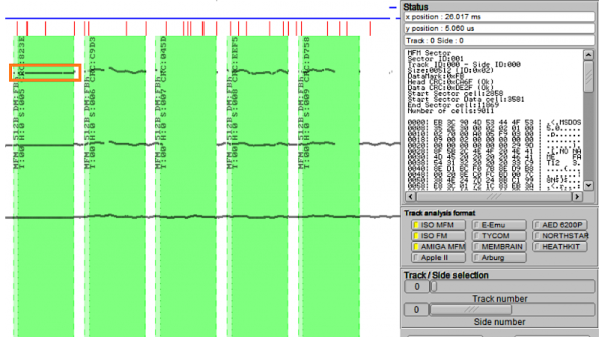

Floppy drives have particularly low-level interfaces, offering up little more than a few signals to indicate the position of the head on the disk, and pulses to indicate changes in magnetic flux. The data is encoded in the pattern of flux changes. This has important implications as far as preservation goes – it’s best to record the flux changes themselves, and create an image of the exact magnetic state of the disk, and then process that later, rather than trying to decode the disk at the time of reading and backing up just the data itself. This gives the best likelihood of decoding the disk and preserving an accurate image of floppy formats as they existed in the real world. It’s also largely platform agnostic – you can record the flux changes, then figure out the format later.

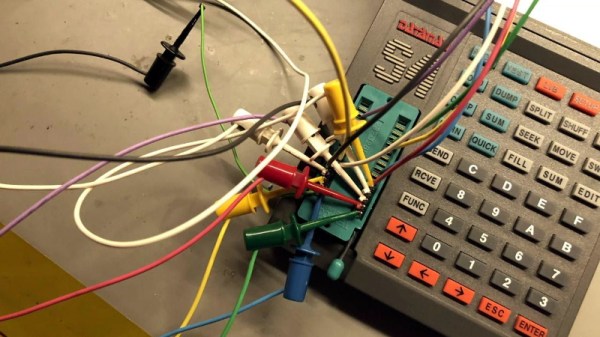

[CHZ-Soft] takes this approach, explaining how to use a Saleae logic analyser and a serial port to control a floppy drive and read out the flux changes on the disk. It’s all controlled automatically through a Python script, which automates the process and stores the results in the Supercard Pro file format, which is supported by a variety of software. This method takes about 14MB to store the magnetic image of a 720KB disk, and can even reveal a fingerprint of the drive used to write the disk, based on factors such as jitter and timing.

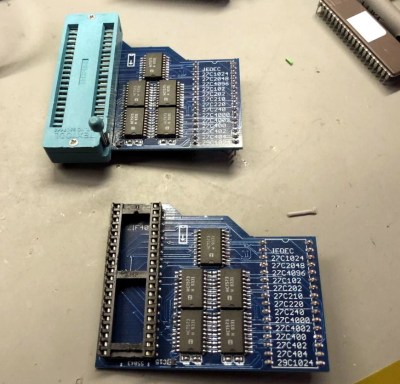

It’s an impressive hack that shows that preservation-grade backups of floppy disks can be achieved without spending big money or using specialist hardware. We’ve seen other projects in this space before, too.