Ever seen a bit of graffiti in a strange location and wondered how the graffiti artist got up there? It might have been a drone rather than an athletic teen. Disney research has just published an interesting research paper that describes the PaintCopter: an autonomous drone fitted with a can of spray paint on a pan-tilt arm. It’s more than just sticking a paint can on a stick, though: they built a system that can scan a 3D surface then calculate how to paint a design on it, and then do it autonomously. The idea is that they want to use this to paint difficult-to-reach bits of theme parks, or to add seasonal decorations without sending someone up a ladder.

Atlas Is Back With Some New Moves

Atlas is back, and this time he’s got some sweet parkour moves to show off. Every few months, Boston Dynamics gives us a tantalizing glimpse into their robotics development labs. They must be doing something right, as these videos never fail both to amaze and scare us. This time Atlas, Boston Dynamics humanoid bipedal robot, is doing a bit of light parkour — jumping over a log and from box to box. The Atlas we’re seeing here is the evolution of the same robot we saw at the DARPA Robotics Challenge back in 2013.

The video caption mentions that Atlas is using machine vision to analyze the position of markers on the obstacles. It can then plot the most efficient path over the obstructions. The onboard control system then takes over and uses Atlas’ limbs and torso for balance and momentum as the robot jumps up and over everything in its path.

It’s interesting to see how smoothly Atlas jumps the offset staircase, leaping left to right from step to step. The jumping is extremely smooth and fluid — it seems almost human. You can even see Atlas’ let foot just barely clear the box on the second jump. We have to wonder how many times Atlas fell while the software was being perfected.

One thing is for sure, logs and boxes may slow down zombies, but they won’t help anymore when the robot uprising starts.

Save A Linotype Machine For Future Generations

The journalist’s art is now one of the computer keyboard and the internet connection, but there was a time when it involved sleepless nights over a manual typewriter followed by time spent reviewing paper proofs freshly inked from hot lead type. Newspapers in the golden age of print media once had entire floors of machinery turning text into custom metal type on the fly, mechanical masterpieces in the medium of hot lead of which Linotype were the most famous manufacturer.

Computerised desktop publishing might have banished the Linotype from the newsroom in the 1970s or 1980s, but a few have survived. One of the last working Linotypes in Europe can be found in a small print workshop in Vienna, and since its owner is about to retire there is a move to save it for posterity through a crowdfunding campaign. This will not simply place it in a museum as a dusty exhibit similar to the decommissioned Monotype your scribe once walked past every day in the foyer of the publishing company she then worked for, instead it will ensure that the machine continues to be used on a daily basis producing those hot metal slugs of type.

Fronting the project is [Florian Kaps], whose pedigree in the world of resurrecting analogue technologies was established by his role in saving the Polaroid film plant in Enschede, Netherlands. There are a variety of rewards featuring Linotype print, and at the time of writing the project is 46% funded with about four weeks remaining. If you are curious about the Linotype machine and its operation, we’ve previously brought you an account of the last day of hot metal printing at the New York Times.

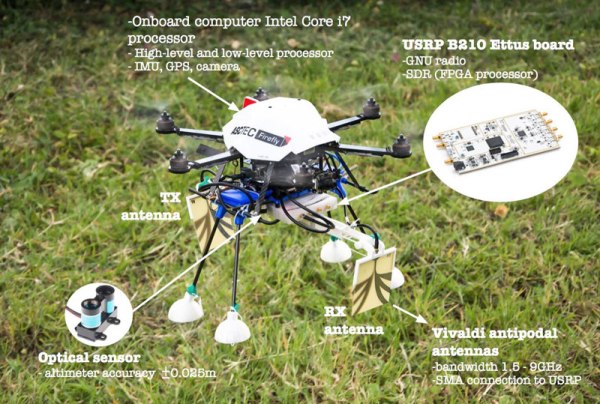

Drone + Ground Penetrating Radar = Mine Detector?

Most civilized nations ban the use of landmines because they kill indiscriminately, and for years after they are planted. However, they are still used in many places around the world, and people are still left trying to find better ways to find and remove them. This group is looking at an interesting new approach: using ground-penetrating radar from a drone [PDF link]. The idea is that you send out a radio signal, which penetrates into the ground and bounces off any objects in there. By analyzing the reflected signal, so the theory goes, you can see objects underground. Of course, it gets a bit more complicated than that (especially when signals get reflected by the surface and other objects), but it’s a well-established technique even though this is the first time we’ve seen it mounted on a drone. It’s a great idea: the drone allows you to have the transmitting and receiving antennas separated with both mounted on pole extensions, meaning that the radio platform can move. Combined with a pre-planned flight, and we’re looking at a system that can fly over an area, scan what is under the ground, and store the data for analysis.

[Via RTL-SDR]

Continue reading “Drone + Ground Penetrating Radar = Mine Detector?”

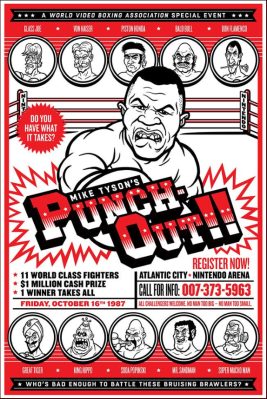

Mike Tyson’s Punchout Patch Gives HDTV Lag A K.O.

They just don’t make them like they used to. Digital televisions have rendered so many of the videogames designed in the days where CRTs ruled the earth virtually unplayable due to display lag. Games that were already difficult thanks to tight reaction time windows can become rage inducing experiences when button presses don’t reflect what’s happening onscreen. A game that would fall into the aforementioned category is Mike Tyson’s Punchout for the NES. However, NES homebrew developer [nesdoug] created a patch for the 31 year old classic that seeks to give players playing on modern displays a fighting chance.

The lag fix patch for Mike Tyson’s Punchout seeks to alleviate some of the display lag inherent in digital displays by adjusting the gameplay speed. Some of the early stages aren’t altered very much, but the later fights incur more significant slowdown to compensate for modern display lag. It’s evident that [nesdoug] is a longtime fan of the game as he also uploaded a remix patch that mixes up the stages and color palettes.

The patch itself comes in the form of an IPS file. To apply the lag fix patch you’ll need an IPS patching tool, like Lunar IPS, along with your own personal backup ROM of Mike Tyson’s Punchout. A checksum value is provided on the lag fix patch download site to ensure you have a usable ROM file. Do note that the ROM file is overwritten in the process of applying the patch, so make sure to put the original file in a safe place. After patching is complete the fun can be had using your favorite NES emulator, or using a flashcart if you’re seeking to play on original hardware.

If you’re looking to dump your own NES cartridges without the plug and play convenience of devices like the Retrode, there is a tutorial in the video below the break:

Continue reading “Mike Tyson’s Punchout Patch Gives HDTV Lag A K.O.”

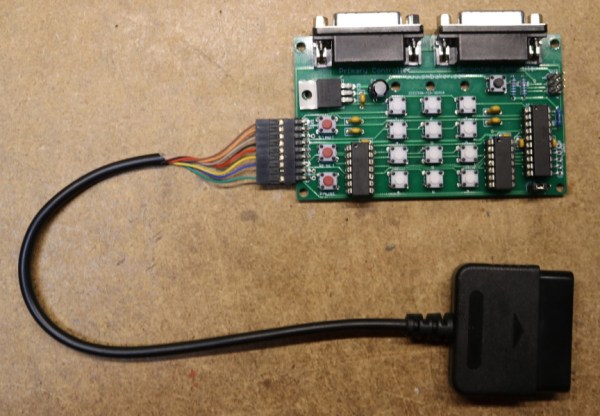

New Controller For Retro Console

In the world of retro gaming, when using emulators and non-native hardware it’s pretty common to use whatever USB controller happens to be available. This allows us to get a nostalgic look while using a configurable controller. One thing that isn’t as common is using the original hardware while still finding a way to adapt a modern controller to an old console. This is exactly what you need though, when you’re retro gaming on a platform with notoriously terrible controllers.

[Scott] enjoys his Atari 5200 but the non-centering and generically terrible joystick wasn’t well received even in the early 80s when the console was in its prime. He decided that using a Dual Shock controller from a Playstation 2 would provide a much better gaming experience, and set about building an adapter. He found that in a way the Dual Shock controller was an almost perfect pairing for the Atari because it has two analog control sticks built-in already. There’s also an array of information on pairing the Dual Shock controller with AVR microcontrollers, so he wouldn’t have to reinvent the wheel. From there, it was just a matter of pairing communications protocols between the two pieces of hardware.

The project page goes into quite a bit of detail on SPI communication protocols and the needs of both the Atari and the Playstation controller. If you’re a retro gaming fan, really into communication protocols, or have always had a love-hate relationship with your Atari because the controllers were just that bad, it’s worth checking out. If this is too much, though, there are other ways to get that Atari nostalgia.

Thanks to [Baldpower] for the tip!

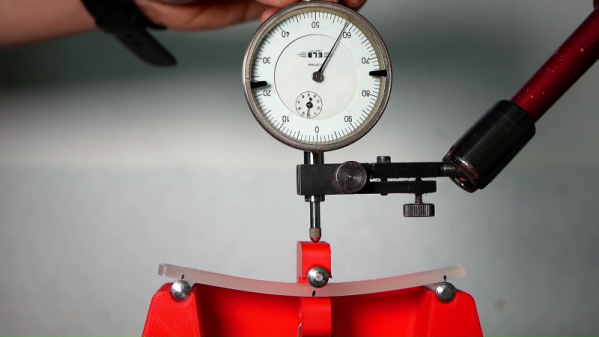

Measuring The Stiffness Of 3D-Printed Parts

How do you choose filament when you want strong 3D-printed parts? Like most of us, you probably take a guess, or just use what you have on hand and hope for the best. But armed with a little knowledge on strength of materials, you might be able to make a more educated assessment.

To help you further your armchair mechanical engineer ambitions, [Stefan] has thoughtfully put together this video of tests he conducted to determine the stiffness of common 3D-printing plastics. He’s quick to point out that strength and stiffness are not the same thing, and that stiffness might be more important than strength in some applications. Strength measures how much stress can be applied to an element before it deforms, while stiffness describes how well an element returns to its original state after being stressed. The test rig [Stefan] built for the video analyzes stiffness by measuring the deflection of printed parts under increasing loads. Graphing the applied force versus the deflection gives an indication of the rigidity of the part, while taking the thickness of the material into account yields the bending modulus. The results are not terribly surprising, with polypropylene being the floppiest material and exotic composite filaments, like glass fiber or even “nanodiamond” reinforced PLA coming out as the stiffest. PLA, the workhorse filament, comes in around the middle of the pack.

[Stefan] did some great work here, but as he points out, in the final analysis it almost doesn’t matter what the stiffness and strength of the filament are since you can easily change your design and add more material where it’s needed. That only works up to a point, of course, but it’s one of the many advantages of additive manufacturing.

Continue reading “Measuring The Stiffness Of 3D-Printed Parts”