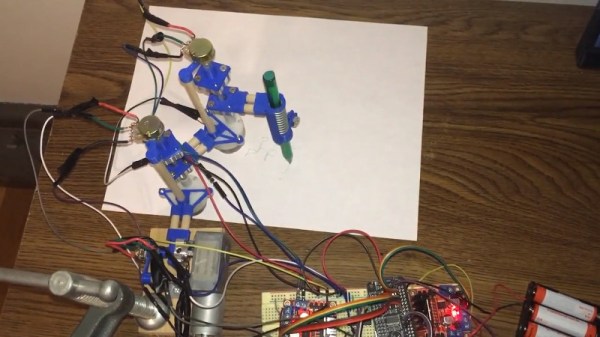

One of the most amazing technological advances found in this year’s Hackaday Prize is the careful application of copper traces turned into coils. We’ve seen this before for RFID tags and scanners, but we’ve never seen anything like what Carl is doing. He’s building brushless motors on PCBs.

All you need to build a brushless motor is a rotor loaded up with super powerful and very cheap magnets, and a few coils of wire. Now that PCBs are so cheap, the coils of wire are easily taken care of. A 3D printer and some eBay magnets finish off the rest. For this week’s Hack Chat, we’re talking with Carl about PCB motors.

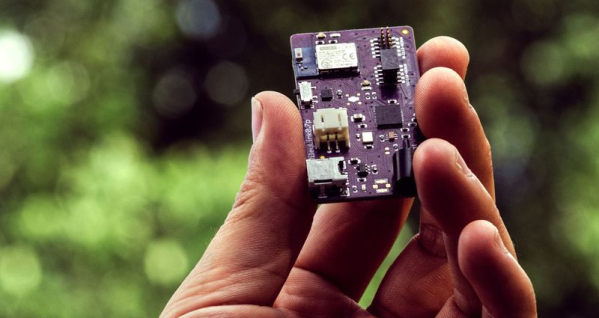

Carl Bugeja is a 23-year old electronics engineer who is trying to design new robotics technology. His PCB Motor design won the Open Hardware Design Challenge and will be going to the Finals of the Hackaday Prize. This open-source PCB motor is a smaller, cheaper, and easier to assemble micro-brushless motor.

Carl Bugeja is a 23-year old electronics engineer who is trying to design new robotics technology. His PCB Motor design won the Open Hardware Design Challenge and will be going to the Finals of the Hackaday Prize. This open-source PCB motor is a smaller, cheaper, and easier to assemble micro-brushless motor.

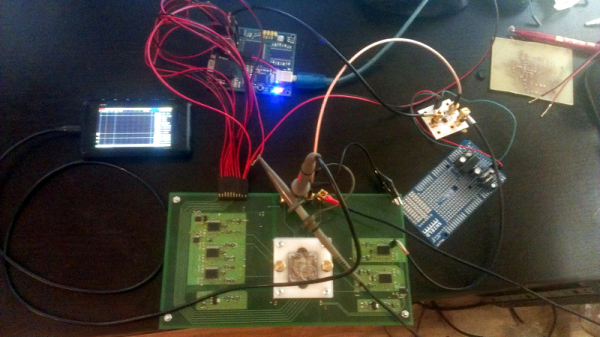

[Carl]’s main project, the PCB Motor is a stator that is printed on a 4-layer PCB board. The six stator poles are spiral traces wound in a star configuration. Although these coils produce less torque compared to an iron core stator, the motor is still suitable for high-speed applications. [Carl]’s been working on other PCB motor designs, like the Linear PCB motor which is a monorail on a PCB and the Flexible PCB actuator where the coils of wire are tucked inside Kapton.

During this Hack Chat, we’re going to be discussing:

- The design and construction of brushless motors

- How to drive these motors

- PCB applications beyond standard circuitry

- Building accessible robotics technology

You are, of course, encouraged to add your own questions to the discussion. You can do that by leaving a comment on the Hack Chat Event Page and we’ll put that in the queue for the Hack Chat discussion.

Our Hack Chats are live community events on the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week is just like any other, and we’ll be gathering ’round our video terminals at noon, Pacific, on Friday, August 10th. Need a countdown timer? You wouldn’t if we switched to universal metric time.

Click that speech bubble to the right, and you’ll be taken directly to the Hack Chat group on Hackaday.io.

You don’t have to wait until Friday; join whenever you want and you can see what the community is talking about.