Self-hosting a few services on one’s own hardware is a great way to wrest some control over your online presence while learning a lot about computers, software, and networking. A common entry point is using an old computer or Raspberry Pi to get something like a small NAS, DNS-level adblocker, or home automation service online, but the hobby can quickly snowball to server-grade hardware in huge racks. [Dennis] is well beyond this point, with a rack-mounted NAS already up and running. This build expands his existing NAS to one which can host a petabyte of storage out of consumer-grade components.

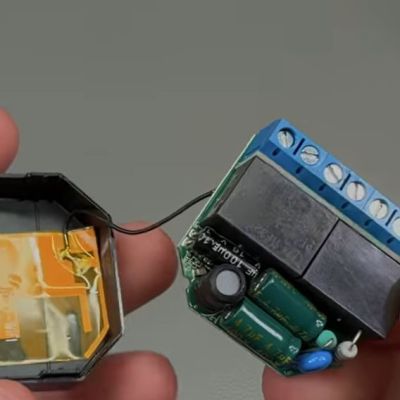

The main reason for building this without relying too much on server-grade gear is that servers are generally designed to run in their own purpose-built rooms away from humans, and as a result don’t generally take much consideration for how loud that environment becomes. [Dennis] is building a lot of the components from scratch for this build including the case, the backplanes for the drives, and a backplane tester. With backplanes installed it’s time to hook up all of the data connections thanks to a few SAS expanders which provide all of the SATA connections for the 45 drives.

There are two power supplies here as well, although unlike a server solution these aren’t redundant and each only serves half the drives. This does keep it running quieter, along with a series of Noctua fans that cool the rest of the rack. The build finishes off with an LED strip which provides a quick visual status check for each of the drives in the bay. With that it’s ready for drives and to be connected to the network. It’s a ton of wiring and soldering, and great if you don’t want to use noisy server hardware. And, if you don’t need this much space or power, we’ve seen some NAS builds that are a bit on the smaller side as well.

Continue reading “A Petabyte NAS Using Consumer-Grade Parts”