Back the late 2000s, when netbooks were the latest craze, some models would come with an inbuilt 3G modem for Internet access. At the time, proper mobile Internet was a hip cool thing too — miles ahead of the false prophet known as WAP. These modems would often slot into a Mini PCI-e slot in the netbook motherboard. [delokaver] figured out how to use these 3G cards over USB instead.

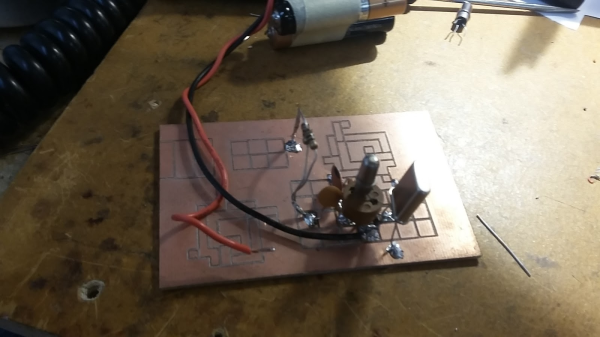

It’s actually a fairly straightforward hack. The Mini PCI-e standard has a couple of pins dedicated to USB data lines, which the modem in question uses for communicating with the host computer. Unfortunately it’s not quite as simple as just soldering on a four-wire USB cable. The modem relies on the 3.3V power from the Mini PCI-e slot instead of the 5V from USB. No problem, just get a low-dropout 3.3V regulator and run that off the USB port. Then, it’s a simple enough matter of figuring out which pins are used to talk to the SIM card, and soldering them up to a SIM adapter, or directly to the card itself if you’re so inclined. The guide covers a single model of 3G modem but it’s likely the vast majority of these use a very similar setup, so don’t be afraid to have a go yourself.

Overall Mini PCI-e is a fairly unloved interface, but we’ve seen the reverse of this hack before, a Mini PCI-e to USB adapter used to add a 12-axis sensor to a laptop.

[Thanks to Itay for the tip!]

![Does [Eben] carry a silver marker with him, laptops for the signing of?](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/archie-with-laptop.jpg?w=300)