The demoscene is a hotbed of masterful assembly programming, particularly when it comes to platforms long forgotten by the passage of technology and time. There’s a certain thrill to be had in wringing every last drop of performance out of old silicon, particularly if it’s in a less popular machine. It’s that mindset that created Don’t Mess With Texas – a glorious megademo running on the TI-99/4A.

Entered in the oldskool demo contest at Syncrony 2017, the demo took out the win for [DESiRE], a group primarily known for demos on the Amiga – a far more popular platform in the scene. The demo even includes a Boing Ball effect as a cheeky nod to their roots. Like any good megademo, the different personalities and tastes brings a huge variety of effects to the show – there’s a great take on vintage shooters a la Wolfenstein in there too. [jmph] shared a few more details on the development process over on pouet.net.

The TI-99/4A wasn’t the easiest machine to develop for. It’s got a 16-bit CPU hamstrung by an 8-bit bus, and only 256 bytes of general purpose RAM. Despite the group’s best attempts, the common 32K RAM expansion present in the floppy drive controller is a requirement to run the demo. Just to make things harder, the in-built BASIC is too slow for any real use and there’s no function to allow the use of in-line assembly instructions. The group had to resort to a cartridge-based assembler to get the job done.

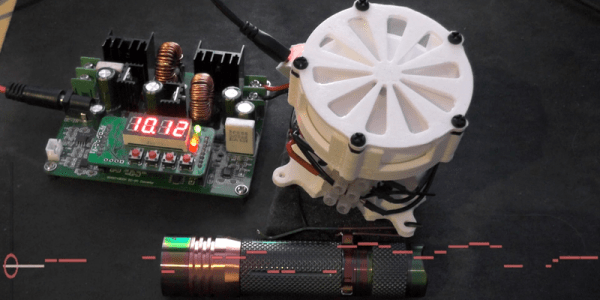

In the machine’s favour, it has a great sound chip put to brilliant use – the demo’s soundtrack will take you right back to the glory days of chiptune. It’s also got strong graphics capabilities for the era on par with, if not better than, the Commodore 64. The video subsystem in the TI works so hard that it’s the only DIP in the machine that gets a heatsink! The demo does a great job of pushing the machine to its limits in this regard.

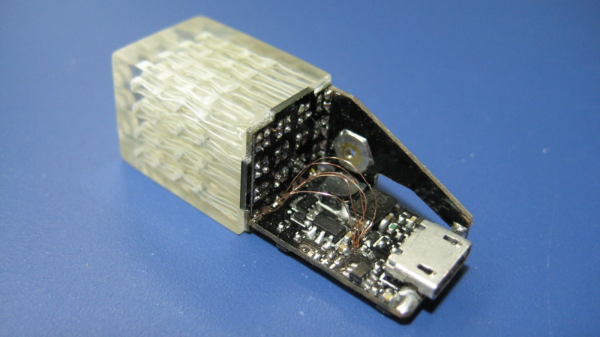

If you’re suddenly feeling a strong attraction to the TI-99/4A, don’t worry – it’s got a cult following all its own. You can even find USB adapters & IDE controllers if you want to build a fully loaded rig, or play a stunning port of Flappy Bird if that tickles your fancy.

[Thanks to Gregg for the tip!]