[Harris Shallcross] decided to build a pair of smart glasses and recently completed a first prototype of his project ‘Ochi’ – an STM32 based, BLE-connected, OLED eyeglass display. There are of course several homebrew smart glasses projects out there; many are more polished-looking and nearly all of them also display information from a smartphone over Bluetooth. This one is interesting partly because it highlights many of the design challenges that smart glasses and other near-eye displays face. It also demonstrates the iterative development process: begin by getting something working to learn what does and doesn’t cut it at a basic level, and don’t optimize prematurely; let the process bring problems to the surface.

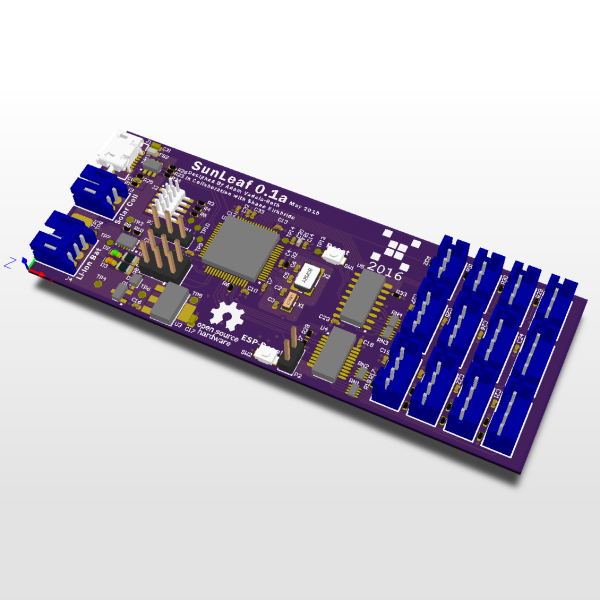

For his project, [Harris Shallcross] used a small 0.95″ diagonal 96×64 color OLED as the display. The lens is from a knockoff Google Cardboard headset, and is held in a 3D printed piece that slides along a wire rail to adjust focus. The display uses a custom font and is driven by an STM32 microcontroller on a small custom PCB, with an HM11 BLE module to receive data wirelessly. Power is provided by a rechargeable lithium-ion battery with a boost converter. An Android app handles sending small packets of data over Bluetooth for display. The prototype software handles display of time and date, calendar, BBC news feed, or weather information.

For his project, [Harris Shallcross] used a small 0.95″ diagonal 96×64 color OLED as the display. The lens is from a knockoff Google Cardboard headset, and is held in a 3D printed piece that slides along a wire rail to adjust focus. The display uses a custom font and is driven by an STM32 microcontroller on a small custom PCB, with an HM11 BLE module to receive data wirelessly. Power is provided by a rechargeable lithium-ion battery with a boost converter. An Android app handles sending small packets of data over Bluetooth for display. The prototype software handles display of time and date, calendar, BBC news feed, or weather information.

Devices like these have a lot to deal with. Weight and distribution of that weight is a concern, the size and comfort of the optics is important, and displaying data on a small OLED is only part of the battle – choosing what information to display and when are vital to the device being actually useful in any way, otherwise it’s just a tech demo.

This project set out to show whether it was possible to use the parts listed to make a glasses mounted smart display that was at least somewhat functional, and the software to support it. Clearly, [Harris Shallcross] succeeded at that, but what really showcases the development process is his list of improvements – what he decided needs to go into a second version, and why. One of those goals is to improve the optics; perhaps there’s something to learn from The $60 Bluetooth Head Mounted Display project, which used a similar OLED and a prism to locate the display off to the side instead of in front.