It’s been a long wait, but our latest single board computer for review is finally here! The BBC micro:bit, given free to every seventh-grade British child, has landed at Hackaday courtesy of a friend in the world of education. It’s been a year of false starts and delays for the project, but schools started receiving shipments just before the Easter holidays, pupils should begin lessons with them any time now, and you might even be able to buy one for yourself by the time this article goes to press.

It’s a rather odd proposition, to give an ARM based single board computer to coder-newbie children in the hope that they might learn something about how computers work, after all if you are used to other similar boards you might expect the learning curve involved to be rather steep. But the aim has been to position it as more of a toy than the kind of development board we might be used to, so it bears some investigation to see how much of a success that has been.

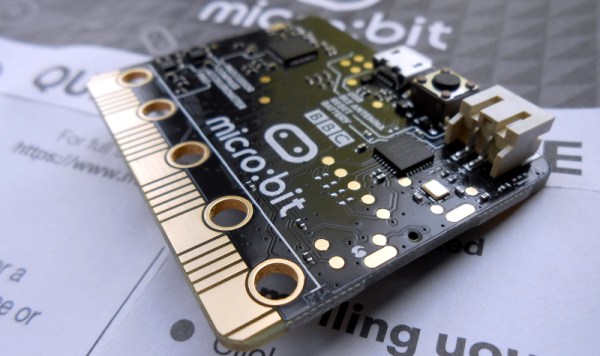

Opening the package, the micro:bit kit is rather minimalist. The board itself, a short USB lead, a battery box and a pair of AAA cells, an instruction leaflet, and the board itself. Everything is child-sized, the micro:bit is a curved-corner PCB about 50mm by 40mm. The top of the board has a 5 by 5 square LED matrix and a pair of tactile switches, while the bottom has the surface-mount processor and other components, the micro-USB and power connectors, and a reset button. Along the bottom edge of the board is a multi-way card-edge connector for the I/O lines with an ENIG finish. On the card edge connector several contacts are brought out to wide pads for crocodile clips with through-plated holes to take 4mm banana plugs, these are the ground and 3V power lines, and 3 of the I/O lines.