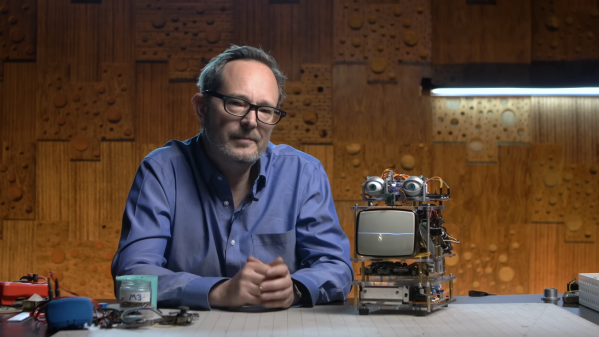

Today, we’re surrounded by talking computers and clever AI systems that a few decades ago only existed in science fiction. But they definitely looked different back then: instead of a disembodied voice like ChatGPT, classic sci-fi movies typically featured robots that had something resembling a human body, with an actual face you could talk to. [Thomas] over at Workshop Nation thought this human touch was missing from his Amazon Echo, and therefore set out to give Alexa a face in a project he christened Alexatron.

The basic idea was to design a device that would somehow make the Echo’s voice visible and, at the same time, provide a pair of eyes that move in a lifelike manner. For the voice, [Thomas] decided to use the CRT from a small black-and-white TV. By hooking up the Echo’s audio signal to the TV’s vertical deflection circuitry, he turned it into a rudimentary oscilloscope that shows Alexa’s waveform in real time. An acrylic enclosure shields the CRT’s high voltage while keeping everything inside clearly visible.

To complete the face, [Thomas] made a pair of animatronic eyes according to a design by [Will Cogley]. Consisting of just a handful of 3D-printed parts and six servos, it forms a pair of eyes that can move in all directions and blink just like a real person. Thanks to a “person sensor,” which is basically a smart camera that detects faces, the eyes will automatically follow anyone standing in front of the system. The eyes are closed when the system is dormant, but they will open and start looking for faces nearby when the Echo hears its wake word, just like a human or animal responds to its name.

The end result absolutely looks the part: we especially like the eye tracking feature, which gives it that human-like appearance that [Thomas] was aiming for. He isn’t the first person trying to give Alexa a face, though: there are already cute Furbys and creepy bunnies powered by Amazon’s AI, and we’ve even seen Alexa hooked up to an animatronic fish.

Continue reading “Animatronic Alexa Gives Amazon’s Echo A Face” →